Two different labor negotiations caught my attention recently and the differences in how they were resolved, (or have not been resolved), paint a nice contrast in how tipping the balance of power in any negotiation continues to be a function of scarcity and ability to add unique, distinct, and not easily replaceable without significant switching costs value.

Exhibit A - The three-month long strike at Caterpillar by the International Association of Machinists and Aerospace Workers.

Points of Contention (simplified and abbreviated) - The company wants the union to accept a new six-year labor agreement, with wages essentially frozen for the duration of the contract, and with workers contributing an increasing percentage of pay towards healthcare costs. The union is countering that in a time of record corporate profits, that the company should not be demanding concessions from the union, and should consider the union and the workers as partners in success, and share more equitably the fruits of a great run of results.

(Likely) Outcome - hard to say for sure, but the recent history of labor actions in the industrial US suggests that Caterpillar management will emerge with all or most of the concessions they are seeking.

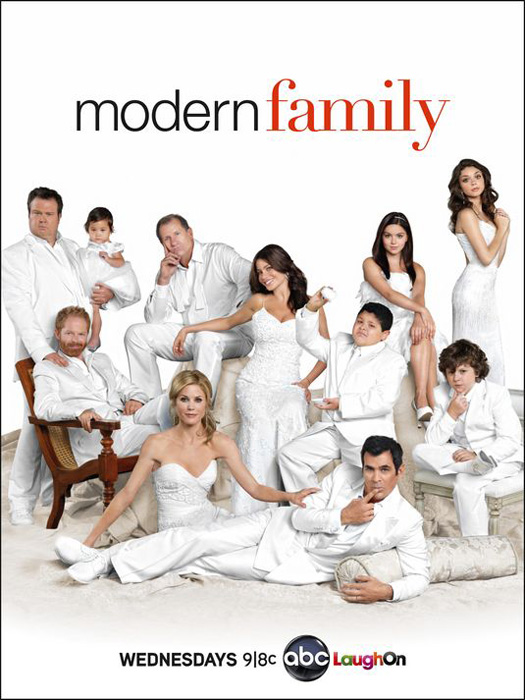

Exhibit B - Adult cast of the ABC TV comedy 'Modern Family' form a united front and stage essentially what amounts to a strike to achieve a significant pay rise for the coming and subsequent seasons.

Points of Contention - The cast, realizing the success of the show, and the strong bargaining position they held, basically wanted to maximize their earnings. The show's producers, also understanding the success of the show, wanted to continue to ride what is often elusive popularity in the entertainment world, while of course, keeping production costs as low as possible so as to maximize the show's profits.

Outcome - The Modern Family cast all won hefty wage raises, although not fully what they were originally seeking. They also won a small stake in 'back-end' money, essentially a form of profit sharing, and agreed to one more year on the contract length than they originally wanted.

The moral to all this?

No, not the completely obvious conclusion that it is better to be a highly paid entertainer than a industrial factory worker, although in many ways that seems true.

No, I think the real story is that no matter what you do your negotiating power, leverage, and ability to extract the absolute best deal in any situation is almost completely a function of how easily replaceable you are. And the corollary is that we now live in a climate with a persistent and stubborn economic slowdown, and where the basic math doesn't seem to make sense.

A world where finding about 800 new and cheaper machinists seems like a more realistic possibility than finding 6 different funny actors.

Whatever you decide to do, better make sure there aren't 800 more just like you waiting for you to slip up or make a tactical negotiating blunder.

Happy Monday!