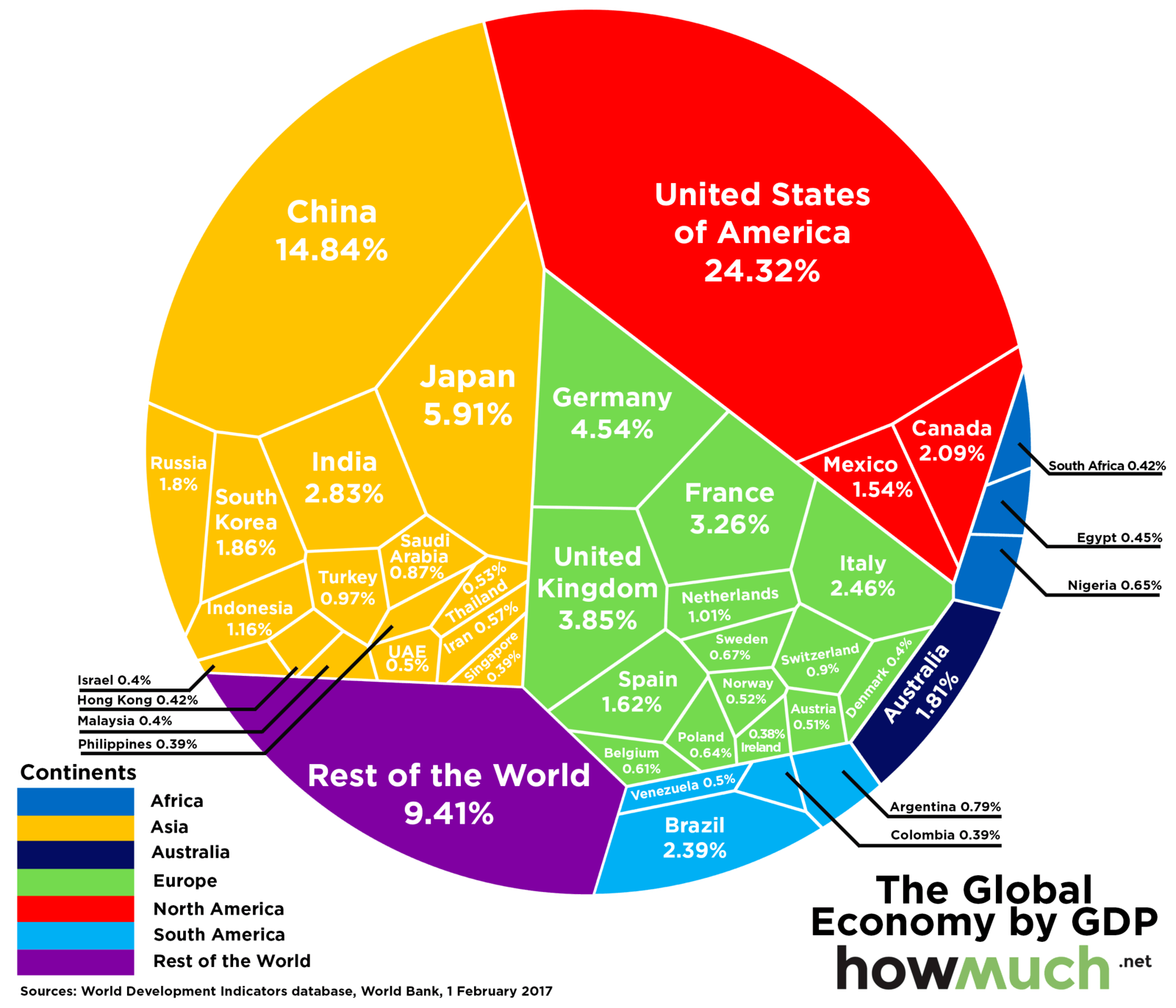

CHART OF THE DAY: The World Economy in One Chart

You may have seen this chart passed around a week or two ago when it was published on Visual Capitalist, but as I was digging through my 'Read Later' pile over the weekend I felt like it was too good and interesting not to share.

So without further delay, visual look at the global economy, represented by country contribution to global GDP, and then as you DEMAND, some free comments from me after the data.

(Email and RSS subscribers may need to click through to see the chart, and clicking on the chart will bring you to a much larger version)

Really interesting and cool chart, right? Three quick observations from me about what 'normals' like us should be thinking about when looking at the data.

1. Go USA! Ok, not trying to be too much of a cheerleader here. But while many other economies (namely China, but I will get to that in a second), have emerged on the world stage in the last twenty or thirty years, the USA still accounts for a shade under a quarter of World GDP. This is important for organizations, particularly US-based or centric organizations to remember even as they make their plans for international expansion. It probably would be a mistake to concentrate too much time and energy on markets that either are relatively small, (say the Netherlands or Spain), or not expected to grow as rapidly in the next ten years, (Germany or the UK).

2. Don't sleep on China, (and to a lesser extent Japan and India). I know that it can be hard for many US businesses to wrap their minds around places like China and Japan. It is hard to to business there. The language and cultural barriers are more significant than say in Western Europe. It may take longer to establish a presence there. But make no mistake, future growth is being defined by what is happening in Asia - not in Western Europe. It may take a little more time, but the organizations that can make the investments, get in front of their competition, will be better equipped to capitalize in the parts of the world that are growing the fastest.

3. Perspective is really the biggest takeaway from a chart like this I think. We can, here in the US, get really full of ourselves,(see above), and it is a good reminder that even as the largest economy, more than 75% of economic activity is happening elsewhere. Insert your own country in the above sentence and the percentages get even more sharp. Places that we think of as economic leaders like Germany and the UK contribute less than 5% each to global GDP, while seemingly set up for being surpassed soon by places like India and South Korea. None of us are all that big a deal.

Anyway, that's it from me for a busy Monday - have a great week!

Steve

Steve