Stack Ranking is somehow still a thing in Corporate America

This week over on CNBC.com a pretty major piece dropped on the workplace culture at Facebook, for years one of America's Top/Best/Greatest places to work, but after a really tough 2018 on a number of fronts, has seen both its market value and its employee morale decline.

There is a ton of detail in the report, but one of the primary contributing factors that led CNBC to describe the workplace culture as 'cult-like', was the company's approach to managing employee performance. Two specific performance management practices were called out for having potentially negative or detrimental impacts on culture and engagement.

The first practice is Facebook's requirement that employees solicit 5 peers at the company to provide feedback on their performance two times a year. This feedback can be given to the employee or to the employee's manager and is kept confidential and importantly, cannot be questioned or challenged. Critics of the process claimed it leads to employees having to make sure they buddy up to a number of colleagues in order to ensure positive feedback only is given, and serves to hide or ignore negative feedback or even just honest and open dialogue.

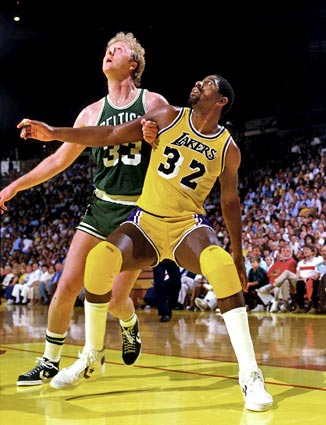

But the second, and probably more important performance management practice in place at the company is a familiar one - the now infamous 'Stack Ranking' of GE and Microsoft fame. Under Facebook's Stack Ranking process, employees are placed (after a lengthy talent calibration exercise), into one of 7 performance categories, with semi-strict percentage quotas and limits for each category being enforced by management.

For example, the top category or highest grade is given to fewer than 5% of employees, while a grade of 'Exceeds' is said to not to exceed about 35% of staff. The CNBC piece cites several anonymous former Facebook employees who indicated that they felt like they had to invent or stress overly negative feedback and comments for employees in order to avoid having too many of their teams in a given performance category - a common problem with just about all Stack Ranking systems.

While in some circumstances and companies (heavy, sales driven ones for example), Stack Ranking can and does work fairly well in setting expectations and managing employee performance. But in complex, creative, technical companies like Facebook, the practice almost always leads to infighting, politics, favor trading, and ultimately, unhappy teams. GE and Microsoft both eventually shifted away from Stack Ranking, it will be interesting to see if this piece and other problems at Facebook will lead them to do the same.

Really interesting stuff and a fascinating look at how a fundamental HR/Talent Management practice is impacting a major organization. It will be interesting to see how it plays out.

Have a great day!

Steve

Steve