A few years ago I wrote about a study that concluded that the optimal day/time to conduct a job interview was exactly 10:30AM on Tuesday.

Back then, I wrote:

Even without data to back up that claim, it at least makes intuitive sense to me. Mondays are terrible for everything. Many folks mentally check out by Fridays. That leaves Tuesday - Thursday as options for any kind of important meeting, like a job interview. Let's automatically remove anything after lunch, as you never know how a heavy meal, quick workout, or a couple of shots and a Schlitz are going to have on the interviewer.

So that leaves Tuesday, Wednesday, and Thursday mornings. Let's rule out Thursday since it is close enough to Friday to catch a little of the 'Is it the weekend yet?' shrapnel. Now we are in a tossup between Tuesday and Wednesday mornings. And since even by only Wednesday, lots of folks might already be thinking 'How can it only be Wednesday, this week is taking forever?', Tuesday seems like a safer choice. As for a time - use the Goldilocks approach - not too early, not too late (and too close to lunch), which lands you at 10:30AM.

Made sense back then I guess. We (the Royal 'We', your mileage may differ), are at our peak of attention, focus, energy, and mental capacity at 10:30AM on Tuesday. So schedule that important meeting, interview, presentation - whatever you need to be at your best for, at that time and you increase your chance for success.

Remind yourself to check back on that at 10:30AM tomorrow, (assuming you read this on a Monday, which is when it is getting posted).

I came across a slightly different version of the 'When are we at our best?' question over the weekend via some research results posted on the Redbooth (a provider of project management software) blog titled 'At what time of day do people complete the most tasks?'.

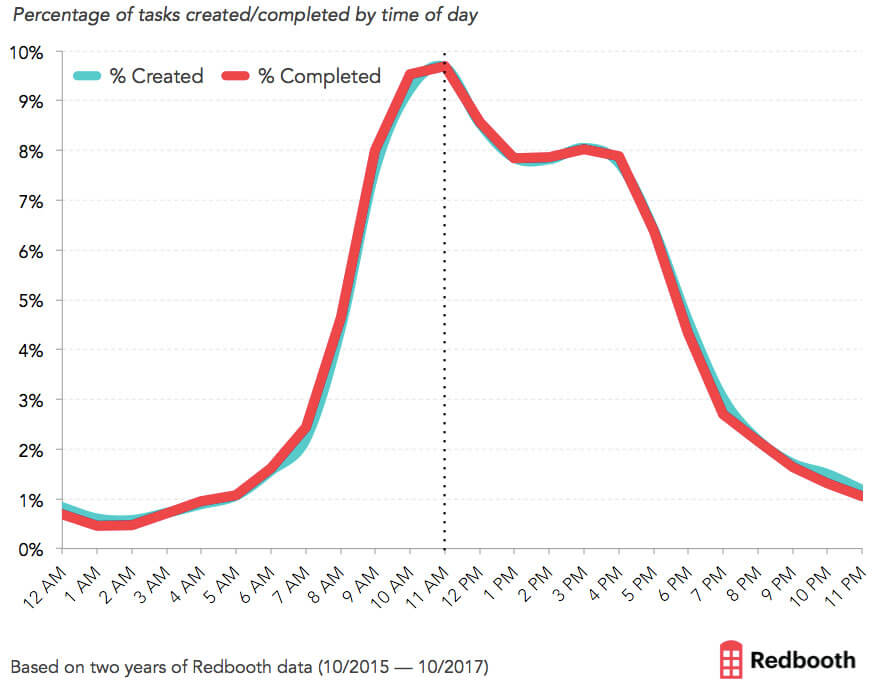

Redbooth studied anonymized data from its user base - over 1.8 million projects and 28 million tasks to try and determine when does work actually get done? Take a look at the chart below that shows what they found about how much work gets done during the typical day.

Kind of makes sense, right? The day starts kind of slow, productivity begins ramping up steeply as the work day progresses and peaks at about 11AM local time (time zones of users were taken into account). Then there is a dip in productivity during the 'normal' lunch break hours that does not really recover as the rest of the day pans out. And around 4PM productivity drops off the proverbial clip and does not recover.

Again, not totally surprising like the answer to the 'When should we schedule the big meeting/interview/presentation?' question.

But a couple of things to note in the Redbooth data that might have an impact on how we plan and perform our work, (and how we manage the folks on our teams).

One, we probably should try no to interrupt our own and our people's most productive times with unnecessary meetings, interruptions, emails, and phone calls. If the sweet spot for productivity is from say 9:30AM - 12:30PM or so, then we should do just about whatever we can to keep that block of time free from distractions and other events that can cause conflicts. Take that standing 10AM Tuesday meeting and think about moving it to 3PM on Thursday, (or consider scrapping it altogether).

Two, the productivity drop is so sharp staring at about 4PM (and continuing through the night and weekends), that we all really need to be honest with ourselves about how much we and our teams are really getting done if we are the kinds that see 12 - 14 hour days and working at least some of the time on the weekends as the norm. The data from the Redbooth platform makes it pretty clear that despite whatever great work we think is getting done at 11PM on Wednesday, it does not add up to much in the data.

And finally, this data suggests or hints at something that many of us have known and research has suggested is true - sustained high productivity over such a large block of time - 8, 10, 12 hours, is really hard for most people to pull off. If we remain committed to the 'standard' working schedule that has dominated for decades, (M - F, 8 hour days, etc.), we should be thinking harder about how we architect work, tasks, meetings, interactions, etc. to try and get the most out of these long days - while not burning out ourselves and our people in the process.

Really interesting data, I think and hopefully helps us to think about how to be better at what we do and what we are trying to do.

Have a great week!

Steve

Steve