Physics, Cities, and Corporations

Last weekend's New York Times magazine ran a lengthy piece titled 'A Physicist Solves the City', in which the physicist Geoffrey West is profiled and his theories that the growth, prosperity, and occasional demise of urban centers can be quantified and analyzed by the correct application of the right equations. Old City

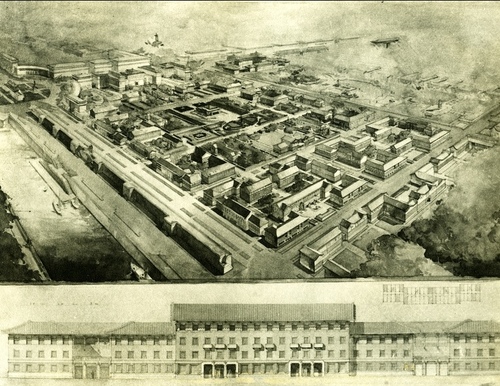

Old City

For example, given the population of a city, West claims to be able to accurately predict the miles of sewer systems and the average income of its inhabitants. The main idea is that beneath the surface differences in architecture, food, and sports teams, is that all cities are fundamentally the same, and once you understand this 'sameness', you can make better decisions for allocating investment and resources for infrastructure and public and social services.

It is an interesting, if long, piece that makes for thought provoking reading. But the most interesting portion of the profile is towards the end, as West turns his attention to the study of the corporation, and more precisely the large corporation. West theorizes that as cities grow they become more successful, mainly by leveraging economies of scale and the relative energy efficiency associate with dense populations. He states, 'In city after city, the indicators of urban “metabolism,” like the number of gas stations or the total surface area of roads, showed that when a city doubles in size, it requires an increase in resources of only 85 percent'. This increased efficiency of resource use is one benefit, but the other, and more apparent one to the city's inhabitants is that big cities make possible more human interactions, frequent opportunity for the exchange of ideas, and development of enhanced collaborative enterprises

Simply put, as cities grow larger, they become more energy efficient and more intellectually powerful via the simple process of jumbling and scrambling lots of people and ideas in a small space.

So you would think the same 'laws' would apply to the corporation, right? Larger organizational size come withs better purchasing power, longer production runs that reduce marginal cost, and the benefits of ideas and innovation that accrue naturally by bringing more and more diverse (hopefully) and talented people together in the corporate context. But according to West, the opposite happens. As companies grow in size, they become less efficient, at least measured by a widely applied metric profit per employee.

From the NYT piece:

West discovered that corporate productivity, unlike urban productivity, was entirely sublinear. As the number of employees grows, the amount of profit per employee shrinks. West gets giddy when he shows me the linear regression charts. “Look at this bloody plot,” he says. “It’s ridiculous how well the points line up.” The graph reflects the bleak reality of corporate growth, in which efficiencies of scale are almost always outweighed by the burdens of bureaucracy.

Why should it be such? If cities, more or less unruly and only lightly regulated places seem to get stronger, more sustainable, and vibrant as they grow, why shouldn't the same general rules apply to corporations as they grow? Why go big companies (generally) seem to stagnate, with ideas and changes taking forever to implement, and exciting new innovations often left to wither and die as they progress from manager to higher manager, from committee to focus group to forgotten?

Again West offers a theory -

Unlike companies, which are managed in a top-down fashion by a team of highly paid executives, cities are unruly places, largely immune to the desires of politicians and planners. “Think about how powerless a mayor is,” West says. “They can’t tell people where to live or what to do or who to talk to. Cities can’t be managed, and that’s what keeps them so vibrant. They’re just these insane masses of people, bumping into each other and maybe sharing an idea or two. It’s the freedom of the city that keeps it alive.

Interesting idea. As cities grow they become more unruly, more free, less managed, and despite all this more successful. As corporations grow they devise and develop more rules, more processes, more top-down control, and erect more barriers in the form of internal structure to random and serendipitous collaboration.

For organizations struggling with growth, or large companies unable to rekindle their agility and excitement of their formative years, could the answer really be to act more like wild, unruly, and insane cities?

Steve

Steve