Learn a new word: The Friendship Paradox

Do you sometimes get the feeling that somewhere there are amazingly cool things being done by seemingly very cool people that you are somewhat connected to and have awareness of due to your Facebook/Instagram addiction?

I mean every time on the weekend when you scroll though your timeline, (in between loads of laundry and cleaning up dog poop), you are treated with images of people laughing at a party, strolling on a white sandy beach, or enjoying another #perfect #sunset with #wine?

Quick aside, and this is for everyone - ENOUGH with the sunset/sunrise pictures. The sun rises and sets EVERY day and everyone has seen this phenomenon thousands of times. We get it already.

Ok, back to the point.

Why is it that it seems like lots and lots of other folks are having an AMAZING time while you, well, not so much?

It could be due to something called The Friendship Paradox. The Friendship Paradox is the phenomenon that your friends have more friends than you do. How does that make sense?

Actually pretty simple, from a recent article on the topic called The Inspection Paradox is Everywhere, by Allen Downey:

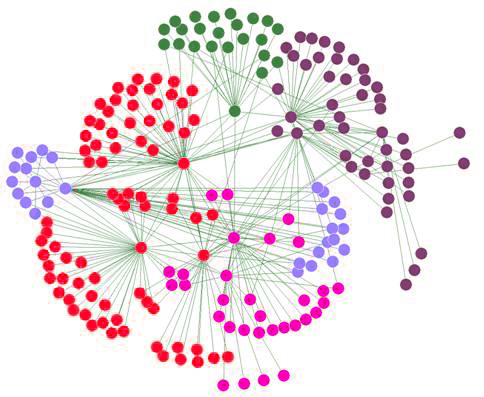

In 1991, Scott Feld presented the “friendship paradox”: the observation that most people have fewer friends than their friends have. He studied real-life friends, but the same effect appears in online networks: if you choose a random Facebook user, and then choose one of their friends at random, the chance is about 80% that the friend has more friends.

The friendship paradox is a form of the inspection paradox. When you choose a random user, every user is equally likely. But when you choose one of their friends, you are more likely to choose someone with a lot of friends. Specifically, someone with x friends is overrepresented by a factor of x.

Ok, so let's accept that the Friendship Paradox is valid, and that for the most part your friends have more friends than you do. But why do they all seem to be happier and to be having more fun than you as well?

Well, it turns out that the Friendship Paradox extends to things like success, wealth, and happiness too.

From a long-ish piece on the MIT Technology Review site titled How The Friendship Paradox Makes Your Friends Better Than You Are:

To study other types of network, Youg-Ho Eom and Hang-Hyun Jo looked at two academic networks in which scientists are linked if they have co-authored a scientific paper together. Each scientist is a node in the network and the links arise between scientists who have been co-authors.

Sure enough, the paradox raises its head in this network too. If you are a scientist, your co-authors will have more co-authors than you, as reflected in the network topology. But curiously, they will also have more publications and more citations than you too.

Eom and Jo call this the “generalized friendship paradox” and go on to derive the mathematical conditions in which it occurs. They say that when a paradox arises as a result of the way nodes are connected together, any other properties of these nodes demonstrate the same paradoxical nature, as long as they are correlated in certain way.

As it turns out, number of publications and citations meet this criteria. And so too do wealth and happiness. So the answer is yes: your friends probably are richer and happier than you are.

That has significant implications for the way people perceive themselves given that their friends will always seem happier, wealthier and more popular than they are. And the problem is likely to be worse in networks where this is easier to see. “This might be the reason why active online social networking service users are not happy,” say Eom and Jo, referring to other research that has found higher levels of unhappiness among social network users.

So if you’re an active Facebook user feeling inadequate and unhappy because your friends seem to be doing better than you are, remember that almost everybody else on the network is in a similar position.

So there you go, you have learned a new word/term and a little bit on the backstory and research behind a phenomenon that you have undoubtedly experienced, maybe even this past weekend.

You were home raking leaves or fixing the leaky bathroom sink or maybe just glued to your sofa watching football and eating chips while everyone else out there was busy being better looking, having more fun, and just living way larger than you.

Except for me. I assure you I was not one of those people.

Have a great week!

Steve

Steve