Sharing the Wealth - NBA Style

Yes, ANOTHER sports-related post.

Cue the groans from the few readers that have not bailed out. I don't blame you. Just give me another shot tomorrow.

This piece isn't REALLY about sports, but rather how an organization's distribution of payroll factors in to contract negotiations, employee movement, and even competitiveness. As basketball fans are aware, the National Basketball Association, (NBA, or the 'association'), is in the midst of an old-school management vs. worker labor impasse. Well as 'old-school' as you can get when the put-upon workers average seven-figure salaries, and the owners who are mostly billionaires, sit on franchise values that seemingly rise every year.

But the owners want to further control and restrict the total compensation available to players. They in the past have managed this by negotiating a maximum total percentage of basketball-related revenue that can be paid out to the players in compensation. The expired labor deal set that figure at 57% of total basketball revenue. Now there are lots of arguments and disputes around the details of the deal, (what exactly constitutes 'basketball revenue' chief among them), and there are more detailed parameters that control how much each team can spend, and even rules around maximum contract values for individual players.

But while percentage of gross revenue paid out in player compensation is the big issue, for teams and players individual compensation is equally important. How the 'pie' is spread inside the league, amongst superstars, solid contributors, and new talent trying to prove themselves is also a critically important angle here, both for the NBA and likely for your organization as well.

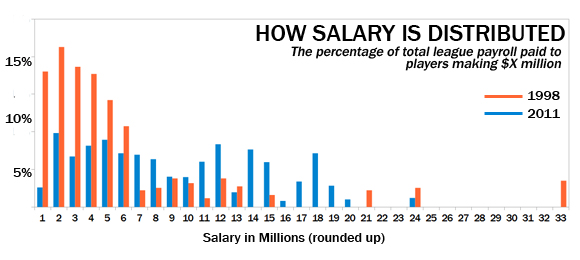

The chart below from a piece on Business Insider shows the relative total allocation of league player payroll across salary levels. For example, if 10 players made $4 million, then $40 million would be dedicated to that salary slot. If total payroll was $1 billion, 4 percent of total payroll would go to $4-million players. The higher the bar, the more total league payroll is expended on all talent at that salary level.

Take a look at the changes in distribution of player payroll by salary level between 1998 (the last year the NBA had labor issues), and 2011:

Two things immediately jump out on the chart. One, in 1998 a much higher percentage of total player compensation was clustered at the lower ends of the salary scale, i.e. in players making $6M annually or less. By 2011, the 'spread' of payroll spend smoothed out quite dramatically, with more players (and payroll spend), moving up the salary chain, particularly in the $10M - $20M range. But almost as strikingly, there has been almost no growth in the extremely high compensation levels - on aggregate, more salary was expended in 1998 on players making above $20M annually than in 2011.

In the 1998 contract negotiations, the owners successfully put in place a system that 'capped' individual contracts in a manner by 2011 has kept current stars like LeBron James from reaching the compensation levels of past stars like Michael Jordan, (represented by the lone orange bar on the far right of the chart).

In the period of 1998-2011, the NBA owners were successful in controlling the extreme high end of the salary scale, but for that, saw salaries at the lower end, and more importantly the middle-range increase dramatically. Over time, contracts awarded to 'solid but not spectacular' contributors have grown out of proportion to those players' contributions to the team's success (with exceptions of course).

One of the primary goals for the owners in this current negotiation is to try and get those mid-range, $6M - $14M or so contracts back under control, while still maintaining the grips on the superstar end of the market as well.

If indeed the NBA owners are in financial trouble, it isn't because the true superstars like LeBron and Kobe make exorbitant salaries, but rather due to the last 15 years of owners overpaying for average performers. Sure, you need quite a few of these 'average' performers to fill out a team, and assembling the right ones with complimentary skills and good attitudes is necessary to actually compete for and win championships, but paying superstar prices for average performance might win you a few games in the short term, but in the long run it will likely tick off the true stars, and might possibly bankrupt the team as well.

I guess that is the challenge for all HR and compensation pros, knowing you need superstar talent to win, and having to spend what it takes to get that superstar talent, while making sure you have enough of the pie left over for everyone else so they won't jump ship chasing a few dollars.

Finally - I promise, no more posts about sports for the rest of the week!

Steve

Steve