One of the most widespread and influential technologies of the last 40 years that has not only improved business but actually helped create entirely new businesses is the seemingly mundane shipment tracking number.

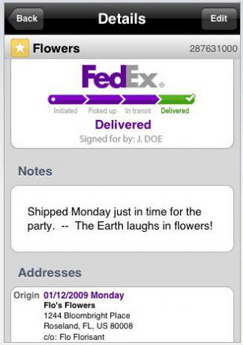

That crazy-long string of 15 or 20 letters and numbers that somehow, as if by magic, allows you to determine the location and stage in the shipment process of all the crap essential items you order from Zappos, Amazon, or Warby Parker. If you are old enough to remember what ordering goods from catalogs or mail-order was really like before the days of tracking numbers then I think you'll agree how dramatic an improvement it is, and how it enables businesses to make commitments and consumers to make plans.

FedEx who recently celebrated their 40th anniversary, created the tracking number and invented scores of related technologies and processes that surround the tracking number which remains the core of their shipment process today. It is a fascinating story of innovation that you can read about in this recent piece on Wired.com, Tracking 40 Years of FedEx Technology.

The tracking number, and the associated network, communications, applications, and database technologies that make the number accessible and intelligent to the shipper, retailer, and consumer alike truly represents an amazing story of technological innovation. But it is a kind of innovation that sometimes we lose sight of, particularly those of us who talk about things like 'enterprise' software - systems like ERP or Supply-chain, or even HCM solutions.

The vast majority of these enterprise systems, and the ones that people (mostly) spent time talking about, are commercial off the shelf solutions. A software company has built these solutions, usually with the insights of customers, partners, and their own internal teams of experts, and then attempts to sell what normally is the same exact system to as many customers as they can. That's the software business, essentially, and it makes tons of sense for both the customer and the vendor.

For the vendor, developing, marketing, maintaining, and updating one main version of the solution is simpler, more efficient, and over time, allows them to spend more time and R&D on building new features and capabilities, which potentially benefit all customers. And for the customer, having to not be in the business of creating their own custom solutions for things like Payroll, Accounts Payable, collecting job applications, and asset tracking is a huge boon as well. For only a very few specialized companies, none of these things are fundamental to their core business models.

But having these types of enterprise off the shelf systems in place, configured, and deployed can only do so much for an organization when you factor in the these two elements - that the same solutions are available to everyone in the market, including their competitors, and mostly the processes they support are not core to their differentiating value proposition. Or said differently, a dozen of your competitors probably run the same ATS as you, that looks and feels kind of the same, and candidates hate theirs as much as they hate yours. No advantage gained, (or ceded, admittedly). Yes you can do a 'better' implementation of generally available solutions, and that might make you a little faster to process an applications or more efficient at taking payment discounts than the other guys, but these kinds of advantages are mostly tangential to whatever your 'real' business is about.

So if true technological competitive advantage is hard to come by simply from commercial off the shelf software, then where can it come from?

Let's go back to the FedEx example. Here's some idea of where from the Wired.com piece:

FedEx’s 40-year history is about far more than an unimaginable number of overnight deliveries. It’s a case study in creating a service, then pushing technology forward to ensure that service actually works on a large scale. When it absolutely, positively has to be there overnight, you need powerful technology. And sometimes you have to create it.

In its relentless pursuit of efficiency, FedEx has pioneered and developed technologies later embraced by everything from cellular industry to online retailing and distributed computing.

“On a day to day basis, shipping 10 million packages, you have to have technology,” (FedEx CIO) Carter said. Even if that means creating it yourself.

The advantage comes from technology that surrounds the essence of the business model - the fast, reliable delivery of customer shipments. The technology that enables that mission, that others can't easily duplicate, is where and how technology helps lead to real success. And all of it had to be created from nothing.

The FedEx technology story really is quite amazing and a great reminder that many of the real innovations in technology, and the differential competitive advantage that can be derived from them, usually starts from a blank sheet of paper, and almost never can be found on any vendor's shelf.

Steve

Steve