Bundling, choice, and basketball

It is a new year, and time for the latest version of what seems like an annual public fight between a big Cable TV company and a high-profile content provider. In the latest example, Cable TV provider Time Warner Cable and the MSG (short for Madison Square Garden), Network are in a pitched battle over the rights fees that Time Warner has to pay to MSG for the rights to distribute MSG programming on its cable systems. As a deal could not be reached by December 31, as 2012 begins the MSG feeds have been blacked out on Time Warner systems.  Blah, blah, blah

Blah, blah, blah

From a purely selfish point of view, the current dispute hits close to home for me - my cable provider is Time Warner, and the MSG Network carries most of the games for my beloved New York Knicks. I admit, the prospect of not having easy access to Knicks games has harshed my Happy New Year mellow.

However, these Cable TV contract disputes provide additional insight to how a combination of escalating programming costs, (mainly in the form of ever-increasing fees paid by networks for the rights to carry professional sports broadcasts); traditional and arcane packaging or 'bundling', and near-monopoly competitive enviroments in many localities have conspired to drive up the costs of basic and enhanced cable rates over the last decade. When ESPN agrees to pay the NFL just over $15 billion over 8 years for the right to show 'Monday Night Football', rest assured the viewers, (and in many cases the non-viewers), of ESPN end up having to pay more to watch Jaws and Gruden gush over how great a job every coach in the NFL is doing.

The end result is a simple and classic pass on the costs gimmick - ESPN and other content providers pay more for their programming, they in turn squeeze the Time Warners and other cable systems for higher per-subscriber fees, and finally the cable systems themselves pass the increased costs down to their customers by jacking up cable rates. Traditionally the cable systems try to mask this process somewhat by their practice of packaging or bundling groups of channels into programming tiers, (Basic, Super Basic, Colossal Super Mega, etc.), that ostensibly provide some consumer choice as to the networks they'd like to subscribe to, and how much they are willing to pay for them. But even the most discrete set of packages or bundles that are generally offered still do not come close to most consumers actual viewing patterns, and likely the set of networks they would order if true a la carte pricing was available in the cable TV industry.

There has been tons written about a la carte pricing for cable TV, and speculation on whether or not it would actually decrease average cable rates. I've seen pretty compelling arguments on both sides, so it is hard to say what the outcome would be. Additionally, any system of individual pricing and ordering of cable networks is generally seen as a death knell for a slew of less popular, niche channels that simply would not have enough viewers willing to pay for them individually to keep them afloat.

Thinking about this entire situation as I have the last few days, (again as it effects my ability to easily watch the Knicks games), I can't help but wonder if this cable TV model is just a refection of a waning and outdated set of assumptions about how content should be created, distributed, and consumed. In an environment where attention, activity, and engagement with content is increasingly shifting to mobile phones and tablets, which themselves are primarily single-purpose application driven, then the idea of consumers choosing to pay monthly fees for 500 channel cable bundles in order to access the 17 channels they are interested in seems like a dying distribution model.

Why can't the MSG network or the History Channel or the hundreds of other channels out there simply create their own an iPad application that would allow consumers to make individual choices about what content they'd like to access and pay for? And to take it a step further, why can't the individual entertainment producers simply skip the traditional networks, cable systems, and satellite providers completely, and market their shows, movies, sporting events, etc. directly to the end user, either with applications or direct streaming or download?

The answer is of course they can, and many are already moving in that direction.

But sadly for me, the era of direct, low friction, and discrete consumption of New York Knicks games has not started as yet. So until then, I get to listen to Time Warner and MSG call each other names.

Steve

Steve

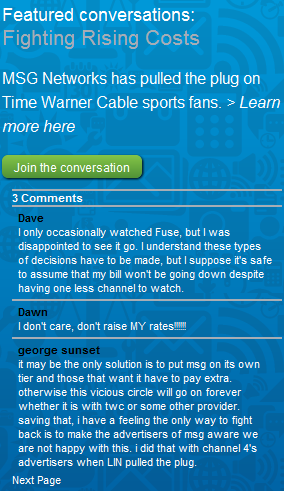

Reader Comments