Maybe engagement isn't the right social outcome after all

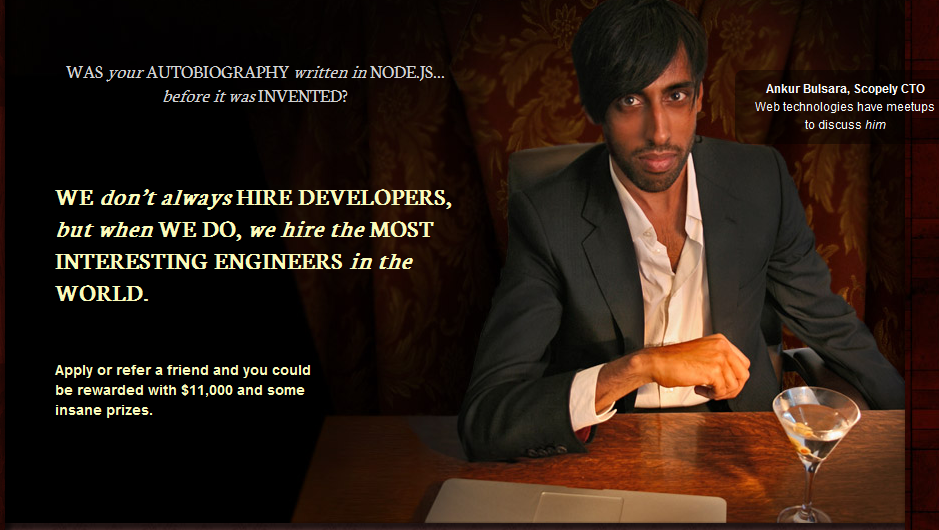

If you have spent much time at all the last few years researching, attending events and presentations, or consulting with experts, (term used very loosely), on how to incorporate social tools and social media into organizational communication, talent management, or recruiting strategy, if nothing else you would have come away with the firm belief that 'engagement' and 'conversation' have to be among your prime objectives and desired outcomes. No customer or potential candidate wants to engage online, the theory goes, be it on a Facebook page, a LinkedIn group, or with a Twitter feed with a faceless organization, a logo, and a stream of automatically generated updates, or worst of all, an RSS feed of job ads pushed to the social outposts from your corporate Applicant Tracking System.  Jasper Johns - #6

Jasper Johns - #6

Conventional social media and social networking advice would tell the organization to simply not bother with social as a channel if all they really plan to do is constantly broadcast, advertise, and push content. You're not ready for social, the experts would say. You have to engage, converse, be a part of a consistent give and take with the audience in order for your efforts to pay off in the long run. And that seems like really solid, sound advice. Consumers and prospects don't want another stream of low-value add corporate messaging and propaganda.

Yep, great advice on how engagement and conversation is what matters.

But what if that advice, if not being completely wrong, is at least not as hard and fast as is generally accepted in the emerging social recruiting space?

A recent ethnographic study on the role of technology and social platforms in the real world from the digital media consultancy Razorfish raises some interesting questions about how average and casual technology users typically consume with and engage with digital content. Long story short, the Razorfish study showed that rather than seeking to actively participate and engage online and with digital media and content, most users were more than happy to passively consume said content. T o some of the study participants, the flow of information in the social space is seen as a more ambient activity and background noise. From the summary of the findings on the Razorfish site:

Historically, digital pundits have promised a more interactive future, in which users move away from passive, couch potato viewing to more active engagement. While the amount of user-generated content and sharing supports this movement, we have found everyday users increasingly leaning back in their digital consumption habits. Social media is described as a more ambient activity. “[Facebook] is usually a drag. I just feel lazy like I’m seeing the same old stuff and looking at people’s profiles. I feel somewhat guilty about it sometimes, like I’m wasting time.” Twitter, originally categorized as a social tool, is described more as a curation tool. “I don’t really tweet anymore. I just see what I should think about reading.”

The folks at Razorfish advise organizations looking to engage with consumers, (in our terms as HR folks employees and candidates), to not be afraid to be a 'pusher', that is to offer content meant primarily to be consumed, and to focus less on stimulating ongoing and sustained conversation. The rapid rise of the the iPad and the other tablets seem to bear this out, they are primarily consumption devices. The little 'creation' that emerges from most tablets are simply shares, likes, and re-tweets, the simplest and most low commitment form of content engagement there is.

The net of all this?

Well the Razorfish study was very small, and certainly should not be the sole data point to base a social content and engagement strategy. But I think an important takeaway from the study is to take a longer and more critical look at both what passes for conventional wisdom in the social media and social networking space, and what can easily become a 'follow fast' strategy that may not necessarily be the right one for your organization.

If nothing else, results from these kind of studies that make us examine carefully our assumptions on what is still a nascent space are worthwhile, and even if you disagree with them, as I imagine many will, occasional validation of your own assumptions is a good outcome in itself.

Steve

Steve