Avatars and office decorations - sometimes little things matter

I've never been one for personal office decorations - family pictures, inspirational posters, desktop golf putting games, etc. I always kind of felt like putting up pictures of the family or the pets on my desk or walls was sort of dumb - after all it was just work, I wasn't going to prison or on some kind of arctic expedition. I'd just seen all these people and animals in the morning, and I'd see them all again that night. I would put a calendar on the wall maybe, but that was about it. And for me, that was perfectly normal and acceptable. If other folks wanted to 'personalize' their work environment with photos and other items, more power to them, I mean to each their own, right?

Except for some folks, and surprisingly even some leaders I have known over the years, my decision to leave my office free from flair was (at least sometimes), interpreted as a demonstration of a lack of commitment to the position and to the organization. For some folks, a colleague that doesn't take the time to put up a few pictures reads to them like someone that doesn't really intend to stay very long, and/or doesn't really care enough about the job to make the space more warm, welcoming, and personal. While I wish that workplaces would be free from these kind of petty and trivial situations, I am also enough of a realist or pragmatist to understand that is often not the case.

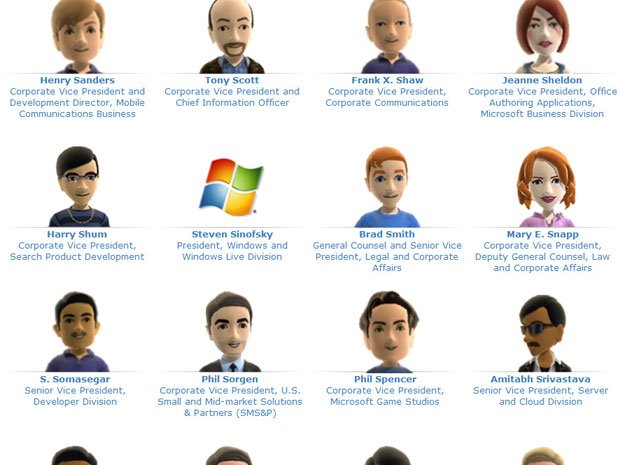

I thought about that former job of mine when I caught this recent piece on Business Insider, A Simple Illustration That Shows How Steven Sinofsky Wasn't a Team Player, about former Microsoft executive Steven Sinofsky, who up until a few weeks ago, ran the huge and lucrative Windows business. Apparently, and for reasons that remain unclear, (probably forever), Sinofsky did not join the rest of the Microsoft executive team by replacing their corporate website headshots with a cutesy Microsoft Kinect-style avatar. Check out the image below, and notice how this lack of participation stands out.

According the BI piece, this seemingly small, unimportant detail spoke to a larger point, that it "symbolized Sinofsky’s reputation inside Microsoft — (he) focused intently on controlling the success of his own division, and not all that interested in playing along with the rest of the company."

Silly right? I mean Sinofsky was an important, busy executive. He probably couldn't be bothered to supply an avatar image, (or more likely, just approve one), for the website. I mean, who cares anyway? What does that have to do with building great products?

I suppose nothing. But somewhere, someone, maybe more than a few folks, interpreted this as Sinofsky's lack of 'buy-in' to the team. It's likely people that felt that way probably felt it all along, and this little example helped to cement their feelings about him.

Either way, and whether we like it or not, sometimes these tiny, insignificant things matter. It would not have killed me to put a few photos up in my office, heck, I could of just bought a couple of new frames and left the stock images they usually come with in them. No one would have known the difference.

But it would have at least made them feel like I was more like one of them, and I was indeed also part of the team.

And that is not insignificant.

Steve

Steve