It's hard to rally around a metric

About a thousand years ago I worked for a large, extremely well-known organization that for a myriad of reasons was going through some tough times. Sales were still good, but expenses were out of control, there were growing quality concerns with some of the most profitable products, and after decades of predictable and recognizable market conditions, changes in the regulatory environment had given rise to a new kind of competitor - smaller, faster, better able to adapt to a much more dynamic market than had previously existed. Got it?

Got it?

Like many large companies that were entrenched and in some ways held captive by their size, history, amount of process and technical debt, there did not seem to be easy solutions, (or at least obvious ones), that the organization could pursue, and more importantly get everyone in the vast value creation ecosystem behind and pulling in the same direction towards, in order to improve results, better position the company for a much different looking future, while continuing to support thousands of customers and employees. As a low-level functionary at the time, I certainly was not privy to all the strategic options our company leaders were discussing to attempt to right the ship, reverse course, clear the anchor, (insert your favorite nautical metaphor here), but I remember well one of the major initiatives that did break free from the board room and impact all of us in the organization.

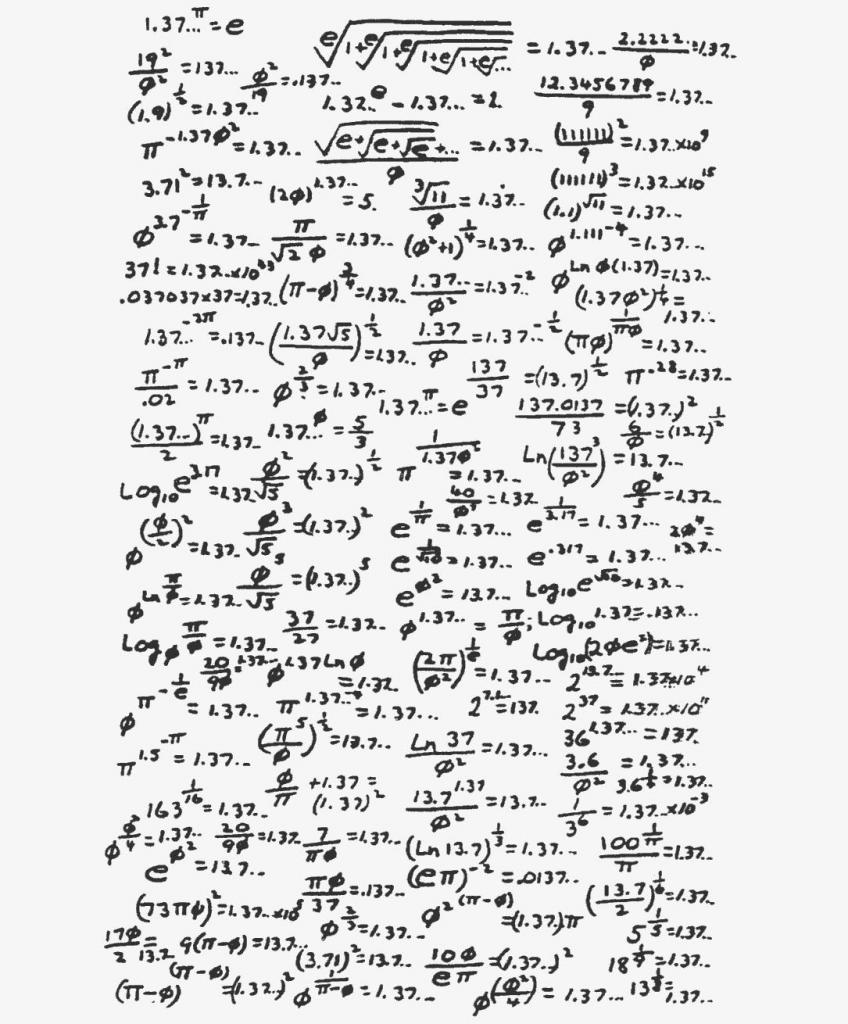

It was that from that point forward, everyone in the company was directed to be focused on a financial measurement called Economic Value Added, or EVA. EVA attempts to estimate a firm's profit, expressed as the value created in excess of the require return of the company investors. EVA is basically the profit earned by the firm less the cost of financing the firm's capital. Confused by what focusing on EVA might mean for the actual people in the organization? Perhaps a quick look at the EVA equation will clear things up:

Ok got it now?

I won't bother listing out what all the variables mean, (check Wikipedia if you are a glutton for punishment). The real point is not that folks in HR or in Talent management need to better understand the real economic drivers of the organization, and the real cause and effect cycles that keep the doors open, the payroll met, and the shareholders happy. There have been oceans of books, articles, blogs, presentations, etc. that all make that same (valid) point. There is general consensus that HR needs to understand the actual business.

But here, and as the little EVA story seems to illustrate, (at least to me), is that in this example HR (and management) needed to understand a lot more than the business metrics. They needed to understand how to connect these metrics, business drivers, and silly-looking equations with what actually would resonate with people, and help them to see the value of the strategy, and help motivate them towards execution of these plans. No one I worked with, for, or near could even really understand at a personal level what focusing on EVA meant to us, or at least was supposed to mean.

Was it cutting costs and expenses? Was it shaving a day or two off a process cycle time? Was it making sure we answered customer complaints in less than 24 hours? Because if those were the things we needed to think about, well, then just tell us that. We could have rallied around saving money, serving our customers better and faster, reducing the energy consumption in the building, or a million other things that were actually real and we could understand and impact.

What we could not do was get excited about an equation, or rally around a flag bearing a formula.

Even if it was the right formula.

Steve

Steve