REPRISE: At least the creative jobs can't be taken over by robots. Wait, what?

Note: The blog is taking some well-deserved rest for the next two weeks (that is code for I am pretty much out of decent ideas, and I doubt most folks are spending their holidays reading blogs anyway), and will be re-running some of best, or at least most interesting posts from 2013. Maybe you missed these the first time around or maybe you didn't really miss them, but either way they are presented for your consideration. Thanks to everyone who stopped by in 2013!

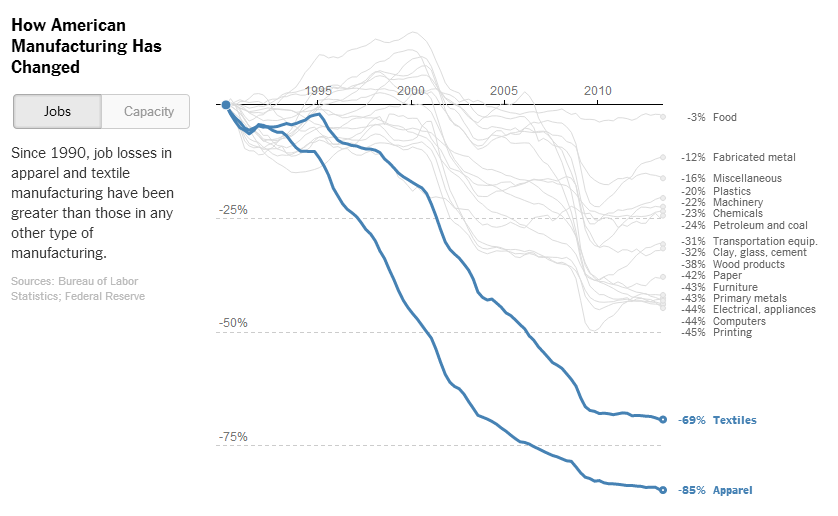

The below post was just one example of the topic I talked about the most in 2013 - the continual and increasing encroachment and pressure that technology and automation is having on the workplace - rendering more and more of us if not obsolete, at least significantly less relevant. The piece originally ran in April 2013.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------

At least the creative jobs can't be taken over by robots. Wait, what?

I know I have beaten the 'robots are coming to take our jobs' angle pretty much to death here over the last few years, and I really want to move on to other things like what we can learn about leadership from Kobe Bryant and the Mamba Mentality, and why Jasper Johns is America's greatest artist, something about the automation of formerly human jobs keeps sucking me back in.

Check this excerpt from a recent piece on Business Insider titled How Facebook Is Replacing Ad Agencies With Robots, about some of the behind-the-scenes machinations that result in those often eerily smart advertisements you see on your Facebook timeline and newsfeed:

Facebook is working furiously to find more ways to make ads work better inside its ecosystem. Many of those ads, however, are untouched by ad agency art directors or "creative" staffers of any kind. And a vast number, from Facebook's larger e-commerce advertisers — think Amazon or Fab.com — are generated automatically by computers.

If you're an e-commerce site selling shoes, you want to serve ads that target people who have previously displayed an interest in, say, red high-heels. Rather than serve an ad for your brand — "Buy shoes here!" — it's better to serve an ad featuring a pair of red heels specifically like the one the user was browsing for.

The ads are monitored for performance, so any subjective notions of "taste" or "beauty" or "style" or whatever go out the window — the client just wants the best-performing ads. There's no need for a guy with trendy glasses who lives in a loft in Williamsburg, N.Y., to mull over the concepts for hours before the ad is served.

It might be easy to miss in that description, but the key to the entire 'no humans necessary' ad creation and display process is a technology that is called 're-targeting' - Facebook (via some partners it works with), knows what products and services you have shown interest in out on the web, and then the algorithms try to 'match' your browsing trail with what the advertiser hopes will be a relevant ad. Since the volume of people and data and browsing history is so immense that a person or people couldn't actually create all the possible ads the process might need, the algorithms do all the work.

So if you stopped at that Rasheed Wallace 'Ball Don't Lie' shirt on the online T-shirt site this morning, don't be surprised if you see an ad for similar on your Facebook feed tonight.

Not a big deal you might be thinking, it's the web after all, and algorithms and machines run it all anyway.

The big deal if you are a creative type person in advertising or media planning is this - if these kinds of re-targeted and machine generated ads show some solid ROI, more and more of the ad budget for big brands will follow. Budget that could be used for TV spots, print campaigns, or even more innovative games and contests on social networks, (that still, for now, have to be hatched and launched by actual humans). If machine-generated ads drive more revenue, (or drive revenue more efficiently), than traditional and expensive creative, then we'll see that impact in staffing.

Traditional ads often run in media where it can be notoriously difficult to determine success - how valuable and how much revenue for a brand like Budweiser can be attributed to an obscenely expensive Super Bowl ad?

But these computer generated Facebook ads? The system can see in real-time how they are performing, which versions of a given campaign are more effective, and they can learn and adapt in reaction to this data. They are smart, so to speak. Almost everything about them from an ad standpoint is 'better' than the creative ad in a magazine or on TV.

Except for the fact that hardly any people are needed to create them. Depending on your point of view of course.

Be nice to the robots.

Career,

Career,  Technology,

Technology,  work tagged

work tagged  Technology,

Technology,  automation,

automation,  robots,

robots,  vacation

vacation  Email Article

Email Article

Print Article

Print Article