Maybe automation will hit managers as hard as staff

Super (long) read from over the weekend on the FT.com site titled 'When Your Boss is an Algorithm' that takes a really deep and thoughtful look at the challenges, pain, and potential of automation and algorithms in work and workplaces.

While the piece hits many familiar themes that have been covered before in the ongoing discussion and debate about the cost/benefits of increased automation for front line workers, (Uber and the like largely controlling their workers while still insisting they are independent contractors, the likelihood of reduced wage pressure that arises from increased scheduling efficiency, and how the 'gig economy', just like every other economy before it, seems to create winners and losers both), there was one really interesting passage in the piece about how a particular form of algorithm might just impact managers as much if not more than workers.

Here's the excerpt of interest from the FT.com piece, then some comments from me after the quote:

The next frontier for algorithmic management is the traditional service sector, tackling retailers and restaurants.

Percolata is one of the Silicon Valley companies trying to make this happen. The technology business has about 40 retail chains as clients, including Uniqlo and 7-Eleven. It installs sensors in shops that measure the volume and type of customers flowing in and out, combines that with data on the amount of sales per employee, and calculates what it describes as the “true productivity” of a shop worker: a measure it calls “shopper yield”, or sales divided by traffic.

Percolata provides management with a list of employees ranked from lowest to highest by shopper yield. Its algorithm builds profiles on each employee — when do they perform well? When do they perform badly? It learns whether some people do better when paired with certain colleagues, and worse when paired with others. It uses weather, online traffic and other signals to forecast customer footfall in advance. Then it creates a schedule with the optimal mix of workers to maximise sales for every 15-minute slot of the day. Managers press a button and the schedule publishes to employees’ personal smartphones. People with the highest shopper yields are usually given more hours. Some store managers print out the leaderboard and post it in the break room. “It creates this competitive spirit — if I want more hours, I need to step it up a bit,” explains Greg Tanaka, Percolata’s 42-year-old founder.

The company runs “twin study” tests where it takes two very similar stores and only implements the system in one of them. The data so far suggest the algorithm can boost sales by 10-30 per cent, Tanaka says. “What’s ironic is we’re not automating the sales associates’ jobs per se, but we’re automating the manager’s job, and [our algorithm] can actually do it better than them.”

The last sentence in bold is the key bit I think.

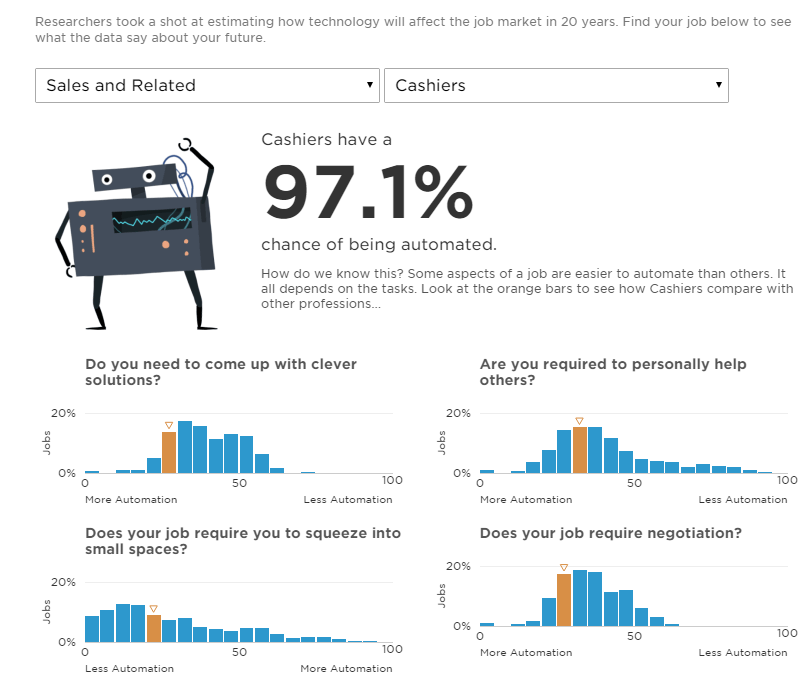

If the combination of sensor data, sales data, and scheduling and employee information when passed through the software's algorithm can produce a staffing/scheduling plan that is from 10% - 30% better (in terms of sales), than what even an experienced manager can conjure himself or herself, then the argument to replace at least some 'management' with said algorithm is quite compelling. And it is a notable outlier in these kinds of 'automation is taking our jobs' stories that usually focus on the people holding the jobs that 'seem' more easily automated, the ones that are repetitive, involve low levels of decision making, and require skills that even simple technology can master.

Crafting the 'optimal' schedule for a retail location seems to require plenty managerial skills and understanding of the business and its goals. And at least a decent understanding of the personalities, needs, wants, and foibles of the actual people whose names are being written on the schedule.

It seems like algorithms from companies like Percolata are making significant advances, at least on the first set of criteria, that include predicting traffic, estimating yield, and devising the 'best' staffing plan, (at least on paper). My suspicion is the algorithm is not quite ready to really deeply understand the latter set of issues, the ones that are, you know, more 'human' in nature.

Or said differently, it is unlikely the algorithm will be able to predict a drop in productivity due to issues an employee may be having outside of work or adequately assess the importance to a good employee of the need to schedule around a second job or some other responsibilities.

There is probably a long way to go for algorithms to completely take over these kinds of management tasks, you know, the ones where actually talking to people is needed to reach solutions.

But when/if all the workers are automated away themselves? Well, then that is a different story entirely.

Steve

Steve