CHART OF THE DAY: Manufacturing Output and Employment

I am sure you have seen something in the news about President-Elect Trump's negotiations with the United Technologies owned Carrier Corp to eliminate or at least reduce Carrier's plans to close and/or reduce manufacturing operations in Indiana, and shift production, (and create jobs), in Mexico. After a bunch of back and forth, (and back and forth), and some finger pointing from both sides, it does appear that Trump's efforts will at least for the time being, keep some of these operations and jobs in the USA.

I don't really want to get into the politics part of this story, but rather want to present some data (from the fantastic St. Louis Fed FRED site), that reminds us that companies packing up and moving manufacturing operations from the US to other, less-expensive places is only part of the reason why US manufacturing jobs continue to be pressured.

Here's the data showing US manufacturing output, (left axis, and indexed to 2009) and US manufacturing employment (right axis) - then some FREE comments from me after the data.

Apologies if some of the fine details of the chart are a little hard to read, but the key things I think to take away from this data are these:

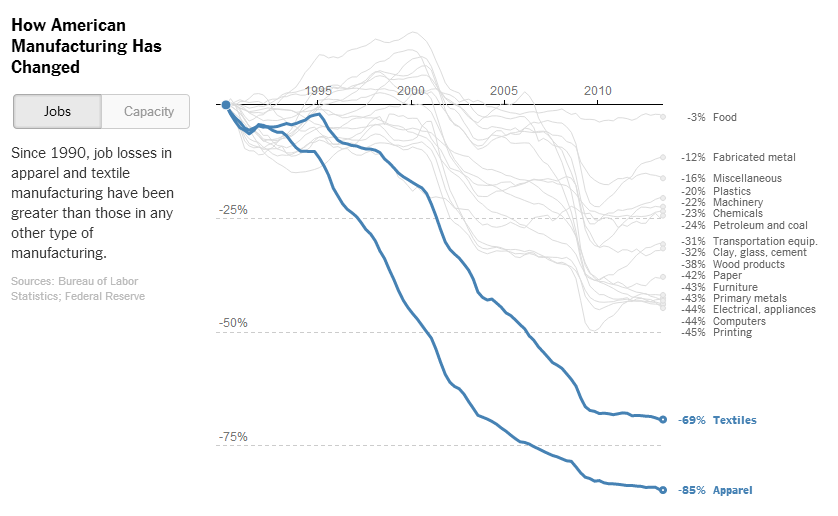

1. Manufacturing employment has been on a steady downward trend since 1980s, with the steepest declines starting in around 2001 (which coincides with an increase in offshoring activity to China and other places); and then again during the financial crisis and recession of 2008. But with the exception of recession-driven dips, manufacturing output has been increasing since the 1980s and is now near its pre-financial crisis level.

In other words, US manufacturers have continued to increase output, and pretty dramatically post-recession, while employing fewer workers.

2. So while outsourcing and offshoring are at least partially to 'blame' for the loss of US manufacturing jobs, those causes can't be the only or even probably the primary driver of manufacturing job loss. Increasing output, with fewer workers means one thing - improvements in manufacturing productivity that have to be attributed to technology, automation, robots, etc. US (and global) manufacturers are simply getting better and more efficient at producing goods, particularly electronics, cars, even steel. Technology gains will continue pressure organizations to 'keep up' with competitors and seek to reduce labor costs via automation.

3. While Mr. Trump's efforts with Carrier probably should be commended, we also should not be beguiled that these kinds of one-off decisions are likely to cause any kind of meaningful or lasting turnaround in the long-term trend of manufacturing job declines. As fast as a thousand ot two jobs might be saved by the application of political pressure, it is also extremely probable that technology/automation will jump in to ratchet up the continued pressure on manufacturers to get even more productive.

Finally, maybe it is time that we start to look a little differently about manufacturing jobs as somehow 'better' or more desirable than other types of jobs. There will always be manufacturing in the US, but as these trends show, it will almost certainly continue to decline as a percentage of the labor force.

Technology-driven shifts in aggregate employment just happen. How many farmers do you know, if you get my meaning. We have to learn as a country and as individuals, to adapt.

Have a great week!

Chart of the Day tagged

Chart of the Day tagged  HR,

HR,  chart,

chart,  data,

data,  labor,

labor,  manufacturing,

manufacturing,  workforce

workforce  Email Article

Email Article

Print Article

Print Article