Grumpy, Chill, Hip, or Out-of-touch - Some new dimensions for your 9-box grid

The classic talent evaluation/assessment/review/calibration process usually looks to position everyone in the group of interest (managers, members of a specific department, everyone having the same type of role), on a 9-box grid that uses 'Performance' and Potential' as its axes.

If you have been in the talent management game for more than say 6 months, you are no doubt familiar with the process of reviewing, assigning, and then taking actions based on where individuals fall on the 9-box. High performer with high potential to advance? Make sure he/she is being given challenging assignments, is being rewarded well, and knows you recognize their value and they have a bright future if they keep up their great work. Low performance and low potential? Maybe it is time to have a frank conversation about whether they remain a good fit in the organization, at least in their current role.

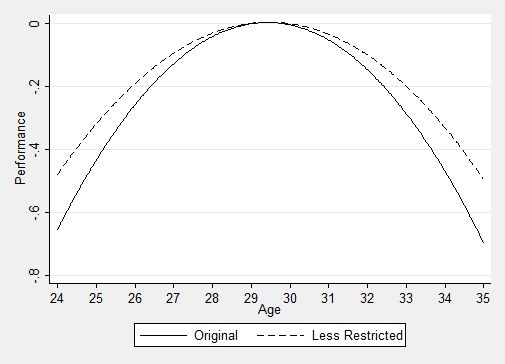

But 'Performance' and 'Potential' are not the only ways or measurements by which to assess and rank a group of employees. In fact, these measurements might not even be the best way to assess a group.  Click for a larger version

Click for a larger version

Take a look at the chart to the right, (courtesy of NBA.com) - a 9-box-like (I know it only has 4 boxes, lay off), that plots the current set of 30 NBA head coaches using 'Grumpy <---> Chill' on the horizontal axis, and 'Hip <---> Out of Touch' on the vertical.

How does one go about assessing Grumpy vs. Chill, or Hip vs. Out of Touch?

Well, here is how the NBA.com piece explains the distinctions?

Grumpy-Chill -- Does the coach seem like a generally cheerful person? Then he's going to be more on the chill side. If he's cantankerous, he's going to be on the grumpy side. This one is pretty self-evident.

Out of Touch-Hip -- This is a little more confusing, since it incorporates coaching strategies, how they relate to players and a wealth of other things. If the coach runs an outdated offense that shuns threes and emphasizes long twos, he's going to end up on the out of touch side. If he can't seem to reach his players, that's also out of touch. But if he's running a "key and three" offense or really understands how to deal with today's players, he'll be on the hip side.

It wouldn't be that hard to make a couple of minor tweaks to the axes and dimensions on the NBA coaches 4-box in order to make it relevant to just about any kind of organization, and in particular, its managers. Grumpy and Chill are pretty much universal concepts no matter what the industry. And grumpy doesn't necessarily equate to 'bad', depending on the context. As for Hip and Out of Touch, this is also a pretty universal continuum. Instead of assessing managers on basketball concepts, just replace them with your organization's version of what constitutes 'hip'. It could be new ways of organizing teams, adoption of new technology, acceptance of variable work styles and preferences - you get the idea. Like most organizations want some kind of a blend of folks on the traditional 9-box, so to you'd likely want at least some Grumpy leaders and maybe a couple that are 'Out-of-touch', as they probably help to remind everyone that 'new' is not always 'better'.

I love the idea of using different, (and hopefully valuable), lenses through which to look at the world. Performance and Potential are good, and have a place in talent evaluation certainly. But they are not the only two dimensions that can be useful in describing people, and they definitely might not be the best ones.

In fact, if I was a front-line worker thinking about joining an organization, or choosing my next assignment, I would be much more interested in where my new manager sits on the Grumpy/Chill/Hip/Out-of-touch matrix than on some Performance Vs. Potential grid.

I actually am not thinking about where I would self-assess on the 'Grumpy/Hip' matrix.

Definitely more on the Grumpy side. But I swear I am pretty hip...

Steve

Steve