What's so great about top talent?

Pretty much every article or analysis of the drivers or pre-requisites for consistent high performance in an organization eventually mentions the concept of 'top talent.'

An organization needs the best or 'top' talent in order to continuously generate great new ideas, to execute their strategies, to improve productivity and efficiency, and so on. Some estimates of the comparative advantage provided by 'top talent' compared to average (and much easier to find) talent rate that advantage as high as a factor of 10. Whatever the actual factor is, and it probably varies pretty widely depending on the industry and type of work, there is pretty much universal agreement that while not always available (and affordable), acquiring 'top' talent should be most organizations goal.

But why, exactly?

What specifically do these 'top' talents bring to the organization? What do they actually do that is demonstrably superior to average talent and how would the answer to that question help organization's improve their recruiting and development strategies?

Well, a recent National Bureau of Economic Research study titled Why Stars Matter, has attempted to identify just what are these 'top talent' effects. It turns out that just being better at their jobs only accounts for a part of the advantage these high performers provide and that possibly the more important benefit is how the presence of top talent impacts the other folks around them, (and the ones you are trying to recruit).

Here is a summary of the findings of the 'top talent' effects from HBR:

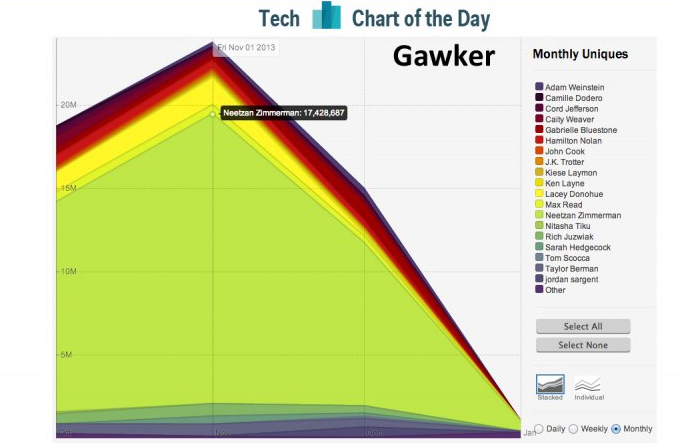

The paper points to three different ways that superstars can improve an organization, and measures the magnitude of each in the context of academic evolutionary biology departments. The first, and most obvious, is the direct increase in output that a superstar can have. Hire someone who can get a lot of great work done quickly and your organization will by definition be producing more great work. But, perhaps surprisingly, this represents only a small fraction of the change that superstars have on output.

The researchers found that the superstar’s impact on recruiting was far and away the more significant driver of improved organizational productivity. Starting just one year after the superstar joins the department, the average quality of those who join the department at all levels increases significantly. As for the impact of a superstar on existing colleagues, the findings are more mixed. Incumbents who work on topics related to those the superstar focused on saw their output increase, but incumbents whose work was unrelated became slightly less productive.

So 'top talent' (mostly) gets to be called 'top talent' because they are simply better, more productive employees. But a significant benefit of these talented individuals is that they help you recruit more people like them, who in turn also are more productive than average, continuing to raise the overall performance level of the organization.

But this only works in the real world if indeed the top talent actually can help you (and actively help you) recruit more people like them.

The findings of the NBER study suggest that beyond their own performance, and the potential of them to elevate the performance of the rest of your team, the real benefit to organizations from 'top talent' is really tied up in whom they help you recruit next.

It might be something to consider adding to your interviewing and assessment process a question something along the lines of "If you were to come on board, who would you recommend we hire next?"

Have a great week!

Steve

Steve