Competing not collaborating - check this before your next leadership retreat

Put enough smart people in the room and you are sure to work out a problem, devise a solution, or otherwise come up with a bunch of great ideas to cure whatever is the crisis du jour at your organization, right?

I mean, it seems like both common sense, and is backed up by most of our personal experiences that if you have a group of intelligent, motivated, and capable folks that at least some kind of solution or direction can be agreed upon. We have all been in these kinds of sessions and meetings - probably hundreds of times. It's not really all that complicated - get the right people together, let them collaborate, and good things generally happen. And usually the 'right' people are ones with some differing yet complementary skills, have a wide range of perspectives, and most of the time, have distinct power levels, either officially or unofficially in the organization. That proverbial mix of generals, captains, and soldiers if you get my drift.

But what happens if the room is filled with only generals - or in your case, a group of leaders who are more or less peers in the organization?

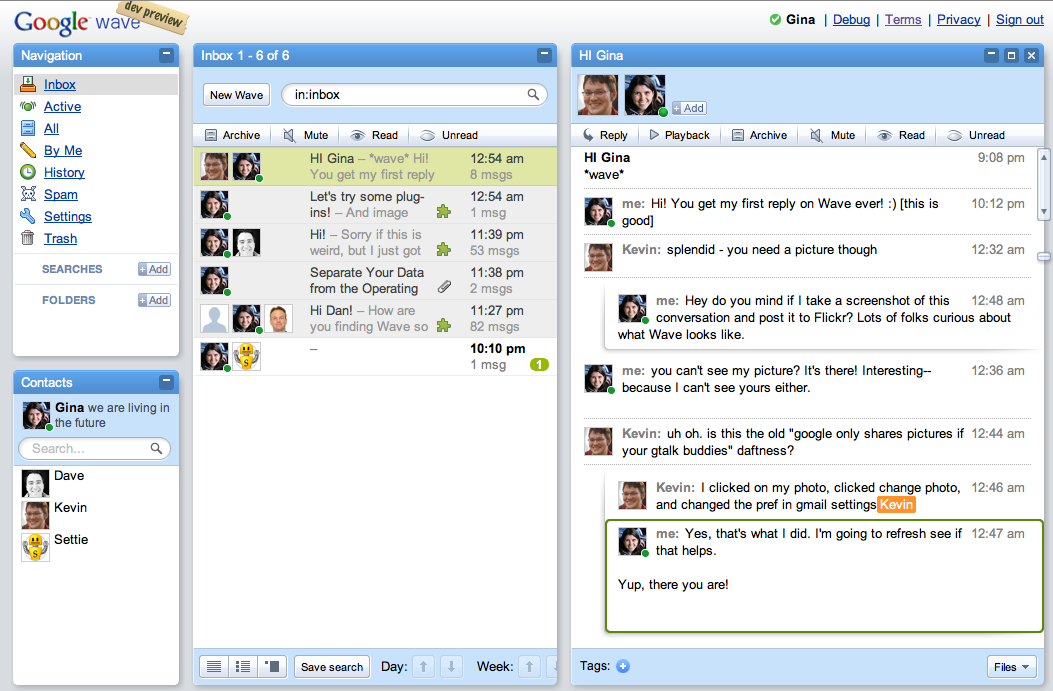

Well, according to a recent study from the University of California and covered in Quartz, it could be that in these 'leaders only' sessions collaboration gives way to competition.

From the Quartz piece:

Corporate boards, the US Congress, and global gatherings like the just-wrapped World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, are all built on a simple theory of problem solving: Get enough smart and powerful people in a room and they’ll figure it out.

This may be misguided. The very traits that compel people toward leadership roles can be obstacles when it comes to collaboration. The result, according to a new study, is that high-powered individuals working in a group can be less creative and effective than a lower-wattage team.

Researchers from the Haas School of Business at the University of California, Berkeley, undertook an experiment with a group of healthcare executives on a leadership retreat. They broke them into groups, presented them with a list of fictional job candidates, and asked them to recommend one to their CEO. The discussions were recorded and evaluated by independent reviewers.

The higher the concentration of high-ranking executives, the more a group struggled to complete the task. They competed for status, were less focused on the assignment, and tended to share less information with each other. Their collaboration skills had grown rusty with disuse.

There's more to the review in Quartz, and of course you can access the full paper here. But the big 'gotcha' from this kind of research is the reminder that just because you assemble the collective 'best and brightest' in the organization to work through some kind of tough challenge, it does not mean that you can assume everyone in the room won't have their competition and self-preservation antenna way, way up.

And it is also interesting to note that the researchers found that while individuals power hampered the group's ability to collaborate effectively, it did not detract from any one individual's ability to reason cognitively. Said differently, the group of leaders studied performed worse collectively that they all would have individually.

Competition at work is sometimes, maybe lots of times, a good thing. It can serve to raise the performance bar in an organization. But be careful what you wish for when you put too many powerful, competitive leaders in a room and expect them to work out the best decisions for the collective.

It's said that power corrupts. It might also be said that too much power in one room amps that power and competitive nature of these people so far that not much good will come from it.

Be careful out there.

Steve

Steve