The three questions to ask when you're thinking of creating something

These notes, taken by Blake Masters from Silicon Valley legend Peter Thiel's Computer Science class on startups, are completely worth reading - whether you work in a startup, are thinking of joining a startup, are thinking of creating your own startup, or just thinking.

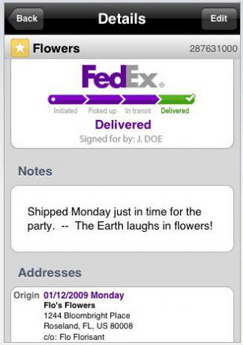

Of the many interesting nuggets and insights in the notes, (the difference and difficulty of taking a brand new idea from 0 to 1, versus taking an idea from 1 to n - with n being infinity and the different stages of technological progress and advancement), I wanted to call out from Masters' notes Peter Thiel's three questions you need to ask when evaluating your idea. Hélio Oiticica, Metaesquema No. 348, 1958

Hélio Oiticica, Metaesquema No. 348, 1958

Here is Thiel's take:

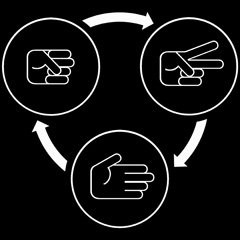

The path from 0 to 1 might start with asking and answering three questions.

First, what is valuable? Second, what can I do? And third, what is nobody else doing?

The questions themselves are straightforward. Question one illustrates the difference between business and academia; in academia, the number one sin is plagiarism, not triviality. So much of the innovation is esoteric and not at all useful. No one cares about a firm’s eccentric, non-valuable output. The second question ensures that you can actually execute on a problem; if not, talk is just that. Finally, and often overlooked, is the importance of being novel. Forget that and we’re just copying.

The intellectual rephrasing of these questions is: What important truth do very few people agree with you on?

The business version is: What valuable company is nobody building?

Earlier in the week I posted about the proliferation of tablet devices that are primarily designed for and used to consume content, rather than create content and the implications of this growth for career management. In a world where people want to consume and consume and consume, I argued, that to have real lasting and sustainable value and advantage that you want to be a creator, not just a consumer. I still believe that, and I also believe it can be really hard for lots of folks to actually create things - blog posts, presentations, podcasts, videos - whatever.

And after reading the notes from Thiel's talk, I think these same three questions about startup formation and practicality of an idea can even be applied to more mundane, or day-to-day scenarios like content creation.

What is valuable?

What can I do?

What is nobody else doing?

Try thinking really hard about those question and you have a start at least or a guide to moving from consumer to creator. And the good thing is for most of us the 'right' answers to those questions can be drawn from a much narrower context than Thiel was probably thinking about (the entire world).

You can probably get by with just finding what is valuable, achievable, and novel in your own company, or city, or industry, or even your group of friends for that matter.

You can be a content creator, and I think, you and definitely your kids, need to become creators too.

Steve

Steve