You call it 'feedback', they hear it as 'criticism'

Let's start with some level setting and definitions:

Feedback (noun) - reaction to a process or activity, or the information obtained from such a reaction

Criticism (noun) - an opinion given about something or someone, esp. a negative opinion, or the activity of making such judgments

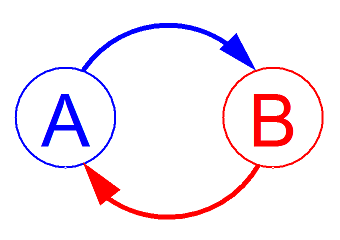

Feedback, especially when you fold in the more technical elements or applications of the term, (like feedback from a machine or from some kind of industrial or mechanical process), more or less connotes neutrality, impartiality, and crucially, accuracy. Sure, sometimes feedback slants negative, but it should be accurately negative, if such a term exists. Because when negative feedback gets interpreted by the recipient of said feedback as being unfairly or inappropriately negative, then it ceases to really be feedback at all, and becomes criticism.

And while most folks seem to appreciate and respect honest, accurate feedback, not nearly as many are down with taking accepting criticism, or for that matter, critics. In fact, many really creative, innovative, and talented folks, the ones everyone is trying to recruit and retain, have little time for critics.

The Finnish composer Jean Sibelius faced plenty of criticism in his career. Sibelius's response to criticism was dismissive: "Pay no attention to what critics say. No statue has ever been put up to a critic."

If you have decided to throw in with the current trend and ditch the annual performance review process (that flawed as it is, has likely served its purpose over the years), you are going to have to get better at assessing how people are interpreting the 'feedback' you and your managers are now laying down on the reg.

One of the main reasons that the traditional performance review process has failed many organizations is that it only provides any kind of feedback to employees on an annual basis. Even if the feedback was kind of terrible, at least the employees only had to endure once a year. So sure, by making the process more regular, more frequent, and less formal solves most of that 'recency' problem.

But more and more regularly scheduled feedback does not by itself make anyone or any manager actually better at giving said feedback. And if more feedback simply adds up to or is interpreted as more criticism, then 'modern' performance management won't be much more effective than traditional performance management has been.

Make sure you are not setting up managers (and yourself) for failure simply by taking an ineffective process, changing its name, and asking people to do it more frequently.

Steve

Steve