What do you think you know about job hopping?

Probably my favorite movie of the last few years is The Big Short, the adaptation of the Michael Lewis book detailing the run-up to the financial crisis/meltdown in 2007 - 2008.

If you have not seen it, take some time this weekend and do so, you will be glad you did.

But why I bring it up is that the movie opens with an on screen quotation, which is attributed to Mark Twain and that reads as follows:

It ain't what you don't know that gets you into trouble. It's what you know for sure that just ain't so.

If you know the story of The Big Short you'll know why the Twain aphorism resonates. Again, take some time this weekend and catch the film if you haven't.

But back to the point, or, rather, here's the point I want to make and why I thought of that quote this week.

What do you think you know about job hopping? Meaning, do you think, as I suspect most of us do, that younger generations of workers, (younger Gen X, Millennials, etc.), are more likely to 'job hop', i.e., have shorter average tenures in their jobs than prior generations?

I mean, that seems to be the convential wisdom, that the Millennials in particular have shorter job tenures, are much more likely than us older types were to leave a job that either is not working out for them, or for what they perceive is a better opportunity, and overall are less attached to workplaces and employers than we were in the past.

Do you think that is more or less true?

I admit, I did, (without ever looking it up), until I caught this piece in the Economist recently, Workers are not switching jobs more often. Here is a quick chart and excerpt from the piece:

EVERYBODY knows—or at least thinks he knows—that a millennial with one job must be after a new one. Today’s youngsters are thought to have little loyalty towards their employers and to be prone to “job-hop”. Millennials (ie, those born after about 1982) are indeed more likely to switch jobs than their older colleagues. But that is more a result of how old they are than of the era they were born in. In America at least, average job tenures have barely changed in recent decades.

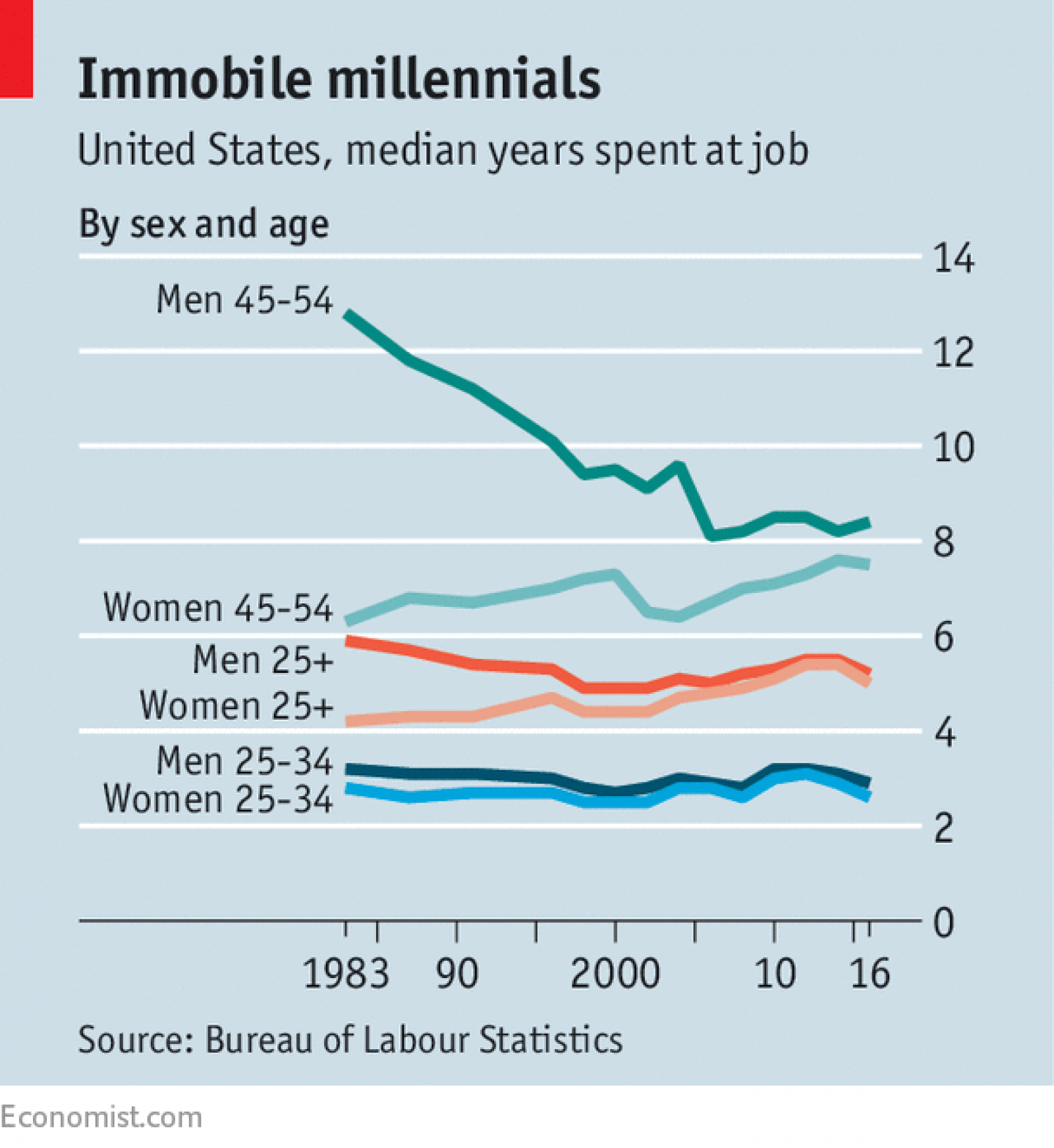

Data from America’s Bureau of Labour Statistics show workers aged 25 and over now spend a median of 5.1 years with their employers, slightly more than in 1983 (see chart). Job tenure has declined for the lower end of that age group, but only slightly. Men between the ages of 25 and 34 now spend a median of 2.9 years with each employer, down from 3.2 years in 1983.

And here is a quick chart showing tenure not really moving, at least at younger cohorts, over time.

So yes, Milennials switch jobs more frequently than older workers. Younger workers have always switched jobs more frequently than older workers. The data shows that the phenomenon hasn't really changed much over the last 30 years.

What's really striking from the chart is not just that the 25 - 34 age cohorts is basically exhibiting the same characteristics with respect to changing jobs than they did 20 or 30 years ago, but that the largest and steepest declines in job tenures are seen in the Men aged 45 - 54 group. That group's average job tenure has declined from 12.8 years in 1983 to 8.4 years by 2016.

There are tons of possibly reasons for this, primarily how the events so well portrayed in The Big Short put so many of this group into unforeseen unemployment, as well as how technology, automation, and outsourcing have seem to affected this group more significantly than other labor cohorts.

But that is a post for another day.

The main reason this one stood out for me is that the data shows pretty clearly that what we think we know for sure, that Milennials are job hopping, low attention span miscreants, probably really isn't true.

What else about work, and careers, and employees do we know for sure that might be, in the words of Twain, 'Just not so?'

Have a great weekend!

Steve

Steve