The Performance Curve

If you are a fan of baseball you might be familiar with the maxim or rule of thumb that states for Major League players that an individual player's performance (hits, home runs, wins as a pitcher, etc.), tends to 'peak' at around age 29 or so (give to take a year or two), then most often declines until the end of their careers.

This phenomenon, most often raised when a team elects to offer hundreds of millions of dollars and 5+ year contracts to players on the wrong side of 30, has been pretty well observed, studied, and documented over the 100+ years of data about Major League player performance.

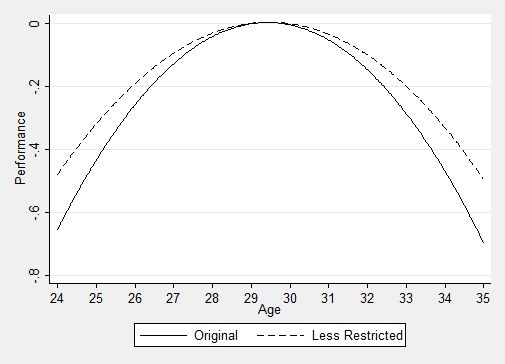

Since charts make everything better, take a look at the generalized performance by age chart from a 2010 study published on Baseball Prospectus:

The specifics of the Y-axis values don't really matter for the point I am after, (they represent standard deviations from 'peak' performance', but simply looking at the data we see for both the original study sample (veteran players with 10+ years of data), and 'less restricted' players, (more or less everyone else), that performance peaks in the late 20s and declines, predicatbly, from there. Keep this data in mind the next time your favorite team drops a 7-year, $125M contract on your best 31 year old slugger. Those kinds of contracts, for hitters or pitchers, almost never work out well for the team. And again, the reasons are completely obvious and predictable. Almost all players skills begin to decline by age 30. All players are in decline by 32.

What does this predictable and observable performance curve for baseball players mean for you as an HR/Talent pro?

I think at least three things can be taken from the baseball performance curve that apply more generally.

1. While baseball, and sports in general, allow more precise and discrete measures of performance that allow us to pinpoint when performance 'peaks', this phenomenon applies in many other scenarios as well. You, or your managers, know after how long in a given role that an employee's performance has likely hit its apex, and continued tenure in that role is likely to results in lessened performance. Put more simply, you can't keep people, especially good ones, in the same roles for too long. They get bored, they figure it all out. And after too long, they start to tune out. The time to move people to the next role isn't when they are on the decline, it is when they are just peaking.

2. In baseball gigantic contracts are often bestowed on players in their late 20s or early 30s, mostly on the basis of several years of prior high performance. While this on first glance seems to make sense, it almost always results in a bad deal for the team And again, the reason is not usually the fault of the player. It is just that 100 years of data show that almost all players are simply not as productive from ages 30-35 as they are from ages 25-30. The lesson here: We need to remember that most compensation should be about ongoing and future performance, and not predominantly as a reward for what has already happened. Past performance is not always, maybe not even all that often, a great predictor of future performance.

3. Baseball player performance is very predictable, as we see in the above data, and there really is no excuse for baseball team management to pretend that is not the case. Decades of data make it plain. I think soon, maybe even fairly soon, the kinds of data and predictive data that organizations will have about employee performance will be similarly robust and powerful. Just as baseball team execs find it very difficult to heed this data, it will be tough for HR and business leaders to 'listen' to their data as well. But the best-run organizations, the ones that make the best use of their resources will be the ones that do not fail to heed what the hard data about performance and people are telling them.

Ok that is it, I am out

Trust your data.

And don't give 32 year old first basemen $100M contracts.

Steve

Steve