CHARTS OF THE DAY: On Increasing Job Openings and Scarce Candidates

Today's chart(s) of the day come courtesy of Gluskin Sheff + Associates, and the excellent (and filled with charts) report from David Rosenberg titled 'The US Labor Market in Pictures, Tighter Than It Looks!', which provides a fantastic overview and re-set of the macro trends for employment in America.

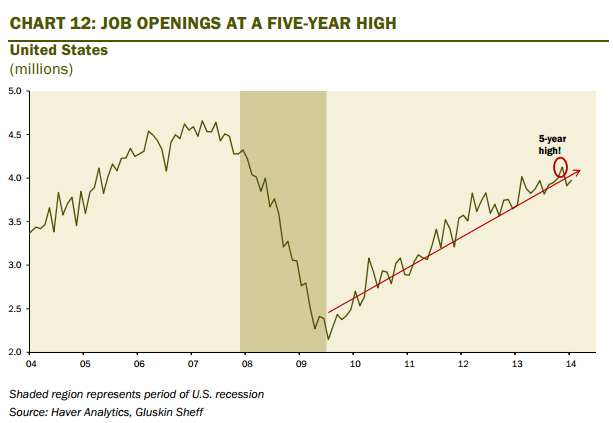

Taken from the Gluskin Sheff report, I want to call out two of the report's dozens of charts, the first on the growth in absolute job openings in the USA:

Job openings continue to rise from the post-recession bottom, and with about 4 million current openings, seem on track to eventually climb to eclipse the pre-recession highs. In fact, if suddenly all 4 million openings were filled from currently (officially) unemployed workers, the unemployment rate would fall to about 4%.

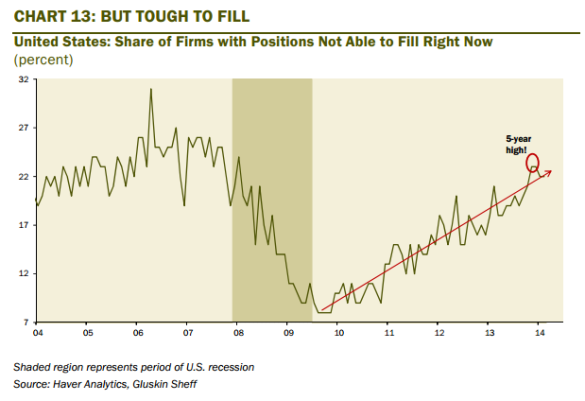

But of course things are not so simple or neat, and this next chart illustrates the challenges that many employers are reporting trying to fill jobs in a time of rising openings:

Companies, especially smaller companies, are reporting increases in 'difficult to fill' positions, (a level just off it's five-year highs), and if you dig into the Gluskin Sheff report further, you will see that over 40% of companies are reporting 'few or no qualified applicants' for their openings.

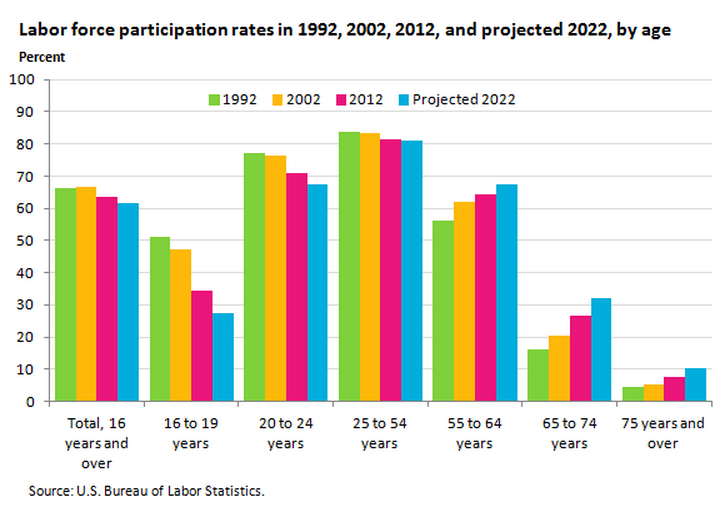

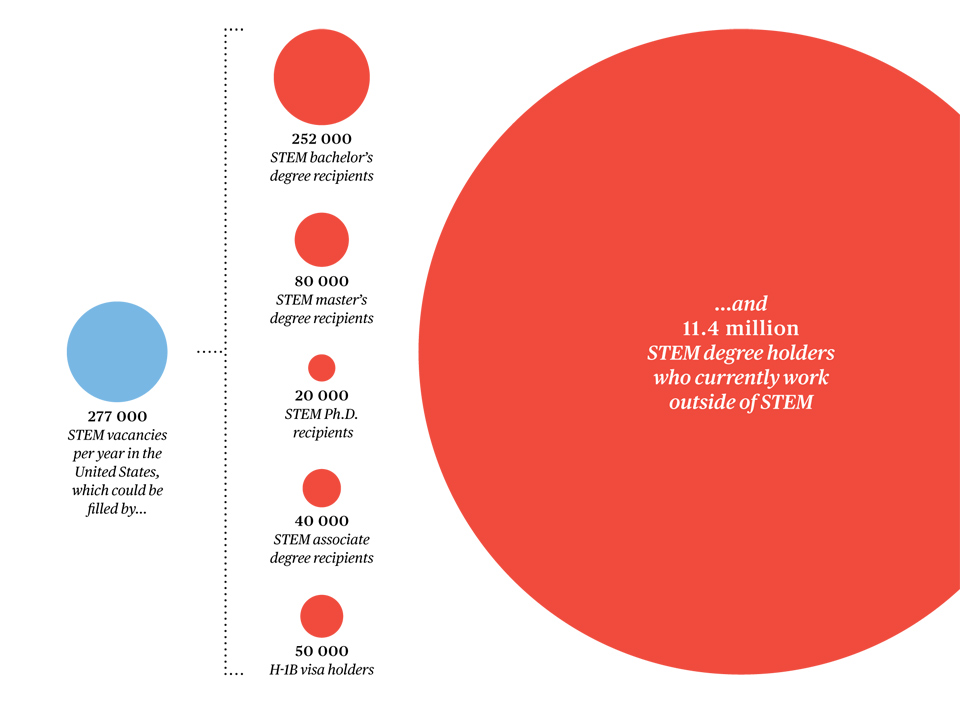

These trends of rising job openings combined with, at least for many types of jobs in many industries, are having a tightening effect on the labor market overall. I am not smart enough to try and tell you exactly why this is happening right now, it is certainly a complex and debatable set of circumstances that includes the aging workforce, the governmental safety net, firm's inability or unwillingness to invest in training candidates, and the 'fake-or-maybe-it-is-not-fake' shortage of candidates with the needed skills for the modern age.

But the data seem to show one thing that is clear - the labor market is starting to show signs of tightening, probably making it more difficult for you in the short and medium term to deliver the candidates you need to sustain your business and talent objectives.

It might be time to start re-thinking all the things that make your shop the place where increasingly scarce candidates want to land.

Happy Wednesday.

Chart of the Day,

Chart of the Day,  ECON 101 tagged

ECON 101 tagged  ECON,

ECON,  chart,

chart,  data,

data,  economics,

economics,  labor

labor  Email Article

Email Article

Print Article

Print Article