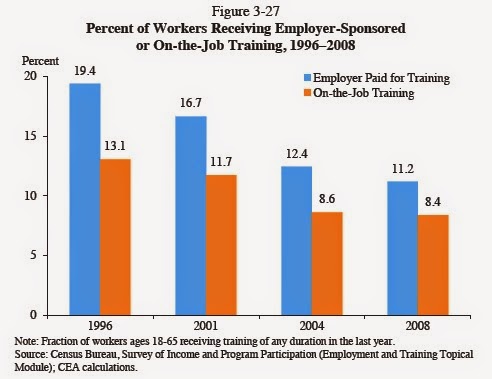

CHART OF THE DAY: The decline of employer provided training

Today's installment of the wildly popular CHART OF THE DAY series offers a selection from some light reading that you can perhaps spend some time with this coming weekend, the 300+ page long 2015 Economic Report of the President.

Nestled on page 147 of this tome, is the below chart - a look at trends in Employer-provided training and on-the-job training opportunities for the US labor force from the period 1996 - 2008 (the latest year this data was available). As always, take a look at the chart, then some witty, wry, and as always FREE commentary from me.

The Chart:

As you can see from the data, both employer paid for and on-the-job training activity, as reported by workers, were both on the decline from 1996 to 2008. And even with 'old' data from 2008, it seems pretty defensible to argue the ensuing few years, the tail end of the recession and the ensuing years of halting economic recovery, that trends and declines in employer paid for training would not have reversed themselves.

As you can see from the data, both employer paid for and on-the-job training activity, as reported by workers, were both on the decline from 1996 to 2008. And even with 'old' data from 2008, it seems pretty defensible to argue the ensuing few years, the tail end of the recession and the ensuing years of halting economic recovery, that trends and declines in employer paid for training would not have reversed themselves.

So, what do we make if this data? Here goes....

1. No one has time or much tolerance for onboarding new people who have to be 'taught' very much, at least taught more general, and transferable from one employer to another type skills. Every job ad you see for say an Accounting Manager just about demands that the person actually already be an Accounting Manager to be considered to get hired as an Accounting Manager.

2. When employers perceive workers to have fewer attractive options outside the organization, the pressure or impetus to invest in upskilling and employee career development tails off. While this is a pretty obvious conclusion, it does not diminish its significance. By 2008 firms, often by financial necessity, had backed way off training and development. That is a short term strategy and decision that can have much greater than expected consequences once times start to improve.

3. Employee training continues to be 'someone else's problem' for many employers. It still is really easy for organizations to demand fully trained and capable candidates for any role prior to hiring, as the fears of costs of training become sunk if and when the employee leaves present a high burden for proponents of more employer provided training to overcome.

4. As an employee, you remain, invariably, on your own. Keep yourself ready, keep current, be willing to pay for it yourself, since fewer and fewer employers are willing to invest in you.

Ack, that was kind of cynical. Sorry.

Happy Thursday.

Steve

Steve