CHART OF THE DAY: We're all getting pretty old

A recurring topic on these Chart of the Day posts for some time now has been the impacts and effects on work and workplaces of an aging population. While in the US the demographic 'time bomb' is not expected to be as extreme as it will be in a place like Japan, there still will be some impact, mainly due to the large Baby Boomer generation exiting the workforce en masse.

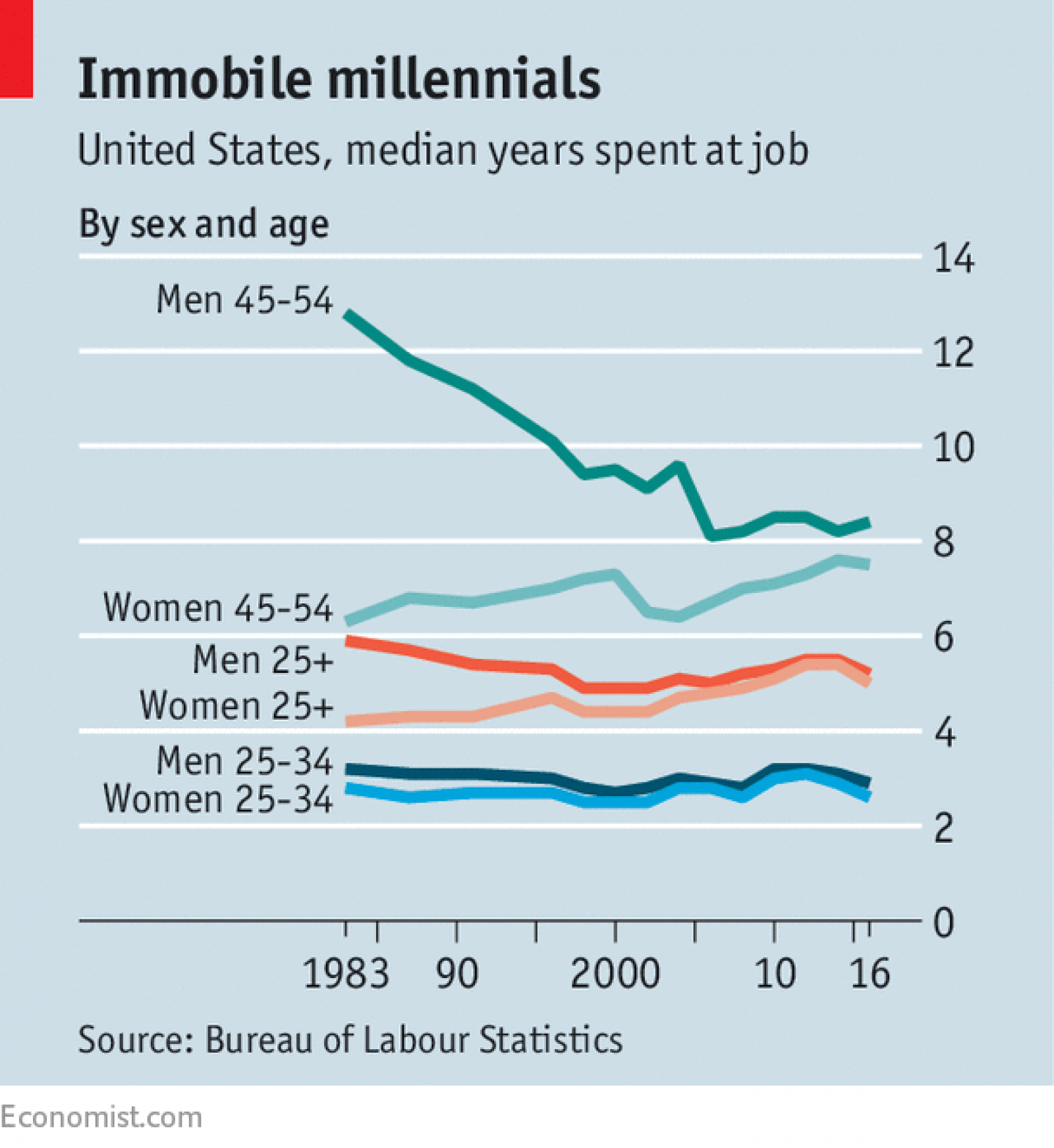

Population pyramids are a cool way to visualize the demographic mix in a place and at a point in time, and the below GIF courtesy of Visual Capitalist presents a moving image of the past and expected US population by age from 1980 - 2050. Have a look (or two or three) at the chart, and then some FREE comments and observations after the data.

Pretty neat, right?

A couple of things stand out from the data. In 1975, the median age in the United States was just 28 years old. However, it’s been rising fast as the Baby Boomers age, and it’s expected to break the 40 year mark by 2030. And just watch in the chart how life expectancy and average age both keep creeping up. Feels like that is a good thing but even still, these trends have some important implications for workplaces, governmental policies, and society overall.

An older population by default means more older workers. Whether it is by need or choice or even employer choice, more and more older workers will be a feature or more and more workplaces. And what older workers, say ones in their later 50s and up will want, need, and expect from work and from employers is by definition much different from what the newest group of college graduate recruits will be looking for.

And while that has probably always been the case, the numbers and increasing age of an organization's oldest workers make that problem or challenge a little tougher than in the past. The mix of ages of the workforce is skewing older, and that has implications for all areas of HR - from training, to benefits, to workforce management and more. And not to mention the need for organizations to be really aware and cognizant of more younger managers, many who lack adequate training and experience in management, wo will be asked to lead and coach more of their older colleagues.

I remain endlessly interested and fascintated by how these macro demographic trends will impact work and workplaces. And this one in particular, as sadly, I, like you, am getting older every day.

Steve

Steve