What the Toys R Us meltdown reminds us about workforce trends

By now you probably have seen the sad news that Toys R Us is in bankruptcy, and is facing the likely closure of its 700+ stores in the US in the coming months.

Definitely a sad day for many, especially for the thousands of Toys R Us employees soon to be out of work, and for the let's say 'traditionalists' among us who still enjoyed shopping for toys and games and the like in the 'real world', and not just from an Amazon app.

Of the many reasons that have been blamed for Toys R Us demise, competition from Amazon (and others) is frequently cited, along with the pretty staggering amounts of corporate debt and debt service payments that Toys R Us has been burdened with since its acquisition by Private Equity companies in 2005. Other post-bankruptcy analyses have pointed to Toys R Us failure to modernize its shopping experiences, inability to grasp digital commerce trends, and the fact that they lost touch with their most important customer - mothers shopping for their kids.

But there is one other factor that has contributed to the toy retailer's plight, one that has not been mentioned as much in the coverage, and one that has much wider implications in work and workplaces as well. And it is this: people in the US are having fewer children, thus creating fewer of Toys R Us' prime 'end customers', and, eventually, fewer entry-level workers for all US firms to recruit.

Here it the thing, the folks running Toys R Us maybe couldn't figure out what to do about this trend, but they did see it coming. Here is an excerpt from their most recent 10-K financial filing from April 2017:

"Most of our end-customers are newborns and children and, as a result, our revenues are dependent on the birth rates in countries where we operate," the filing reads. "In recent years, many countries' birth rates have dropped or stagnated as their population ages, and education and income levels increase. A continued and significant decline in the number of newborns and children in these countries could have a material adverse effect on our operating results."

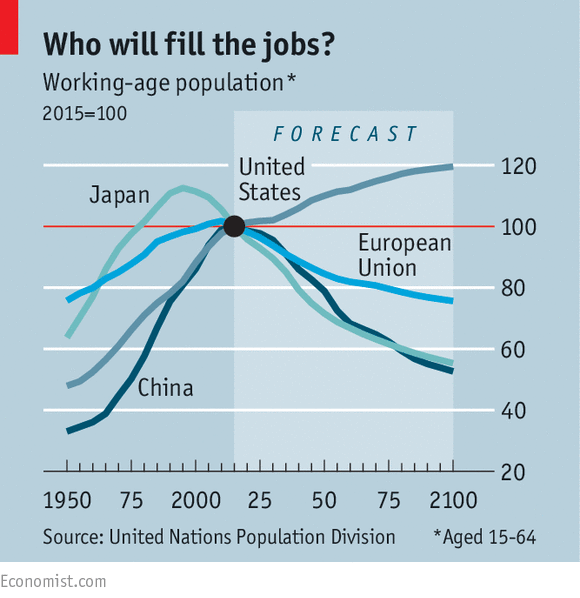

Data from the CDC in the US backs that up - the most recent data available from 2016shows the US birth rate hitting a record low, and with no obvious sign of this trend changing, retailers like Toys R Us are going to face continuing pressure. Longer term, if this trend does continue, all kinds of employers will face pressure too - a different kind of pressure perhaps, this one stemming from relatively fewer entry-level or younger candidates, as well as the need to create workplaces that are more open, accommodating, and available to older workers too.

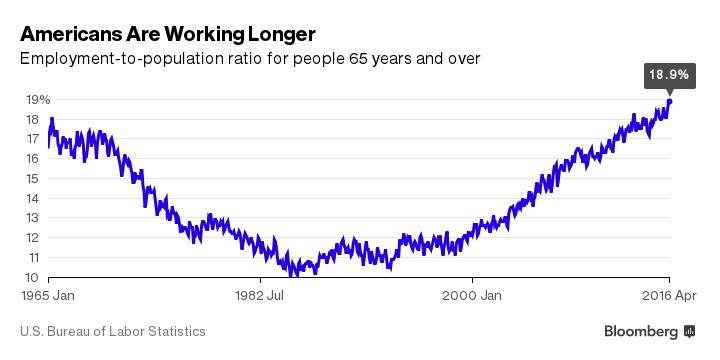

Since I love charts, I will close with this one, from our pals at FRED - a look at the increase in the 65+ labor force in the US over the last 20 years or so.

I will spare you trying to squint at the small print, but the total number of workers aged 65+ has more than doubled since 2000 - with almost 10M people in that group as of the latest data. And even if you can't read the small print, it is easy to see the 'up and to the right' trend in the data.

Fewer babies and young kids means trouble for Toys R Us in 2018. It could mean recruiting problems for your organization too, in a few years. Don't wait until it is too late, like our pals at Toys R Us, to know how to react.

Have a great week!

Steve

Steve