Tenure and Unhappiness at Work

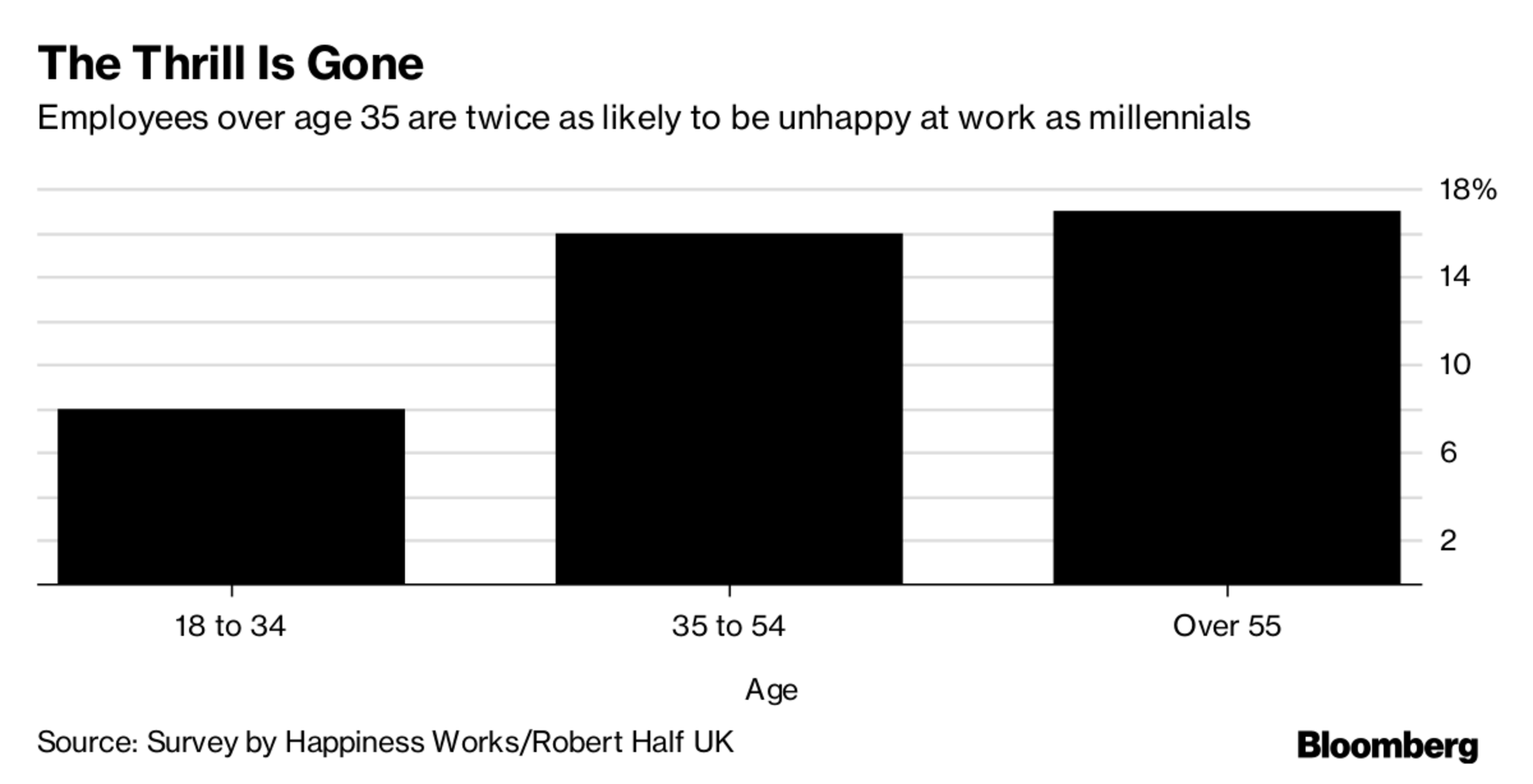

Caught some interesting data looking at the happiness and satisfaction with work of employees in the UK broken down by different age cohorts. As reported in Bloomberg, UK workers aged 35 years and up were twice as likely to be unhappy with work as their younger, millennial colleagues.

Here's a quick look at one data set from the research conducted by Happiness Works and Robert Half UK about employee unhappiness distributed across age groups:

According to this data, unhappiness at work takes a pretty decent sized step up in the 35 to 54 age group and increase a bit more with the 55+ group. Couple of small/medium/big things to think about before we take this data totally at face value.

One is just what do we mean by 'unhappiness?' Is it 'kind of had a bad day that day' unhappiness or is it 'I am about three minutes away from quitting and smashing the printer on the way out the door' unhappiness? And second, what is the 'normal' or expected amount of unhappiness we'd expect to find in an average workplace? I can't think of any scenario when you get a large group of people in any kind of shared endeavor where some of them wouldn't be happy. Even a few folks I heard from yesterday thought the Great American Solar Eclipse was a little underwhelming.

But getting past those concerns for a second, let's think about the implications of increasing unhappiness as the workforce ages a bit more. If true, or even kind of true, this could be an issue for more and more workplaces and more and more leaders of HR and people.

Here's some more data, courtesy of my pals at the BLS. From 2015, a quick look at the median age of the US workforce, and some projections out to 2024

How about that? The US labor force is trending older, and the trend is expected to hold for the next decade if not a little longer. So if workforces are getting older and unhappiness with work seems to be associated with the employee's age, then you could expect even more acute challenges to come with respect to happiness and its cousin employee engagement.

The problem of course with aging in the workforce is that it is pretty similar to our own personal battles with aging and its effects. It happens, or seems to happen, so gradually that we hardly even notice it. And then Wham! all of a sudden we have gotten older. And we usually are not prepared for that day.

If you are someone who has some concern or responsibility for the health, wellbeing, happiness, and productivity of a workplace you probably ought to be thinking about these issues a bit more than you have in the past.

And it probably wouldn't hurt to take time to think about your own happiness and wellbeing too.

Steve

Steve