When things don't work out: Lessons from the New York Knicks

My beloved New York Knicks wrapped up a disappointing 2013-2014 season last night with a win, but despite the win and some solid play in the season's late stages the season ended with a playoff-missing 37-45 won-loss record.

Since I spent a ridiculous amount of time this season watching the Knicks I better have gotten something out of it (or I will be really even more depressed), so I figured I would share five quick lessons from disappointment from the 2013-2014 Knicks debacle of a season. Knicks coach Mike Woodson, in his standard 2014 repose

Knicks coach Mike Woodson, in his standard 2014 repose

1. Be careful with celebrations and self-congratulation

Last year the Knicks had a surprisingly strong season, winning 54 games and also winning their first playoff series in about 20 years. They were eliminated in the second round of the playoffs, but still went out with a feeling of "We've had a great season!" But the good feelings and accomplishments from a prior success don't really mean anything when it comes to tackling the next challenge. This year's Knicks team had a lingering hangover from the celebrations of prior accomplishments that themselves were not all that great. Lesson? Don't celebrate too long and especially for 'wins' that are not all that remarkable.

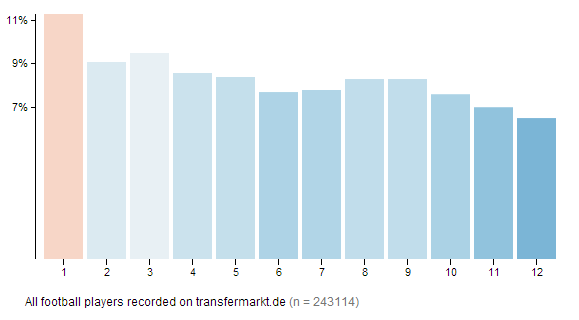

2. Sometimes you are the worst evaluator of your own capability and potential

Prior to the season, a computer analysis of their prospects predicted the Knicks would finish with a 37-45 record, and miss the playoffs. And that prediction was predictably mocked and derided by the team's players and coaches. But as we see, this is exactly the terrible record the Knicks ended up with. The lesson here? When a neutral, no-skin-in-the-game third party (like this computer), gives you an assessment of your performance and capability, you should at least consider its point of view and findings. Like the Knicks, most of us are pretty bad at self reflection and examination.

3. You can't fix other people's problems

One of the major off-season moves the Knicks made was to acquire via trade former Toronto Raptors forward (and former 1st overall draft choice from 2006), Andrea Bargnani. In Toronto, Bargnani was essentially hated, and the Raptor fans even made celebratory videos when his trade to the Knicks was announced. While Bargnani might be a nice guy, he is not a very good NBA basketball player, despite 'seeming' like he should be (he's tall). Bargnani's performance with the Knicks, (before getting injured and missing the last half of the season), was almost exactly in line with his career average performance level from seven years in Toronto. Bargnani was a mediocre-at-best player that the Knicks somehow felt in their system could perform at a higher level. The lesson is that they were wrong.

4. Past performance is not indicative, except when it is

Last season's 54 win Knicks team was powered, in part, due to career-best performances by two players, Point Guard Raymond Felton, and shooting guard and NBA 6th Man of the Year, J.R. Smith. For various reasons, both of these player's performances were substantially better than their career averages, and consequently helped lead the Knicks to what was really an over performing 2013 finish. In 2014 instead of repeating that level of relative over achievement, both players regressed back to their typical or expected performance levels, (and at times, even below that). They both returned to who they are. Your takeaway? Veteran employees don't usually and suddenly start performing much better or much worse than their career history suggests. And when or if they do, you can expect a return to the mean level of performance (good or average) eventually.

5. When things are really bad, you have to send a message

Towards the end of what would be a lost season, the Knicks signed NBA coaching legend (and former Knicks player) Phil 'Zen Master' Jackson to be the team's new President. While this was too late in the campaign to make much of a difference in 2014, at least it sends a message to the team, the fans, and the other execs that the Knicks are at least finally realizing they are a dysfunctional mess. Will Jackson be able to actually turn the Knicks around next year? Hard to say but the lesson from ownership to the team and for you as well is clear: When there is a performance problem, you can't expect it to just work out on its own, you have to take some steps to shake up the organization, the culture, the staff, etc. in order to get at and improve the problems.

Ugh, I am just as drained from this (silly) post as I have been watching this disaster of a Knicks team this season. But talking/writing about it is a little cathartic, I think. I guess that is the last lesson from this terrible team - no matter how bad things get it helps to vent a little bit about it.

Have a great day!

Steve

Steve