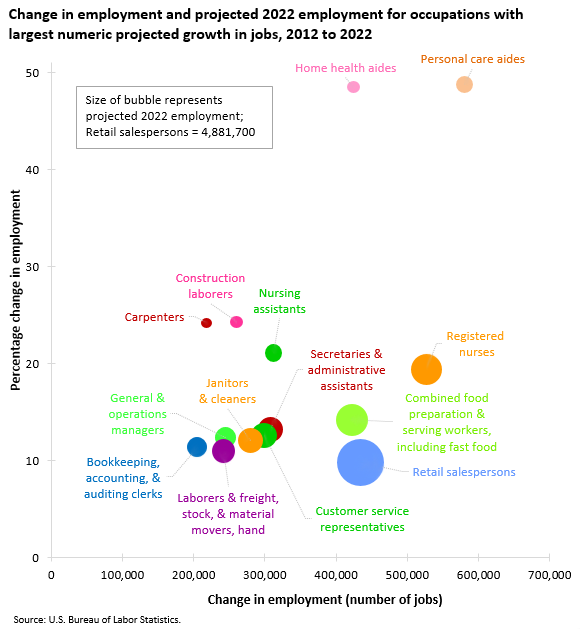

CHART OF THE DAY: Where the new jobs are projected to be

Once again from our friends at the Bureau of Labor Statistics, today's chart is all about jobs - more specifically a look at in which occupations the BLS is forecasting the greatest numerical growth in jobs for the ten-year period of measurement, 2012 - 2022.

Take a look at the chart, then (of course) a few comments from me afterward:

Digging in to the data a little bit more (and taking into account the sheer difficultly in making these kind of far out into the future sorts of projections), reveals both some warnings, and some surprises.

First off, something that is not surprising, is that of the 30 areas projected to experience the largest employment increases, 5 are in healthcare, including 3 of the top 4 jobs that are expected to see the greatest increase, (personal care aides, registered nurses, and home health aides).

Combined, the top 5 healthcare related occupations are projected to add 1.6 million jobs over the 2012–2022 decade.

But while the growth in healthcare jobs is not surprising, given the pressures being put on the healthcare system due primarily to an aging population, what is surprising is what the BLS suggests about the educational attainment needed by workers desiring to actually work in these faster-growing occupations.

From the BLS sumary:

Two-thirds of the occupations projected to add the most new jobs typically require a high school diploma or less, while only five typically require a bachelor’s degree.

Now that little observation is, to me at least, a little surprising, or perhaps just a little misaligned with everything that we typically see about the importance of higher education as it relates to a candidate's job prospects. But upon closer examination of the BLS job growth projections, perhaps we should not be that shocked at all.

The care aides kinds of jobs, the retail jobs, the food prep and serving jobs, the customer service reps, (all in the Top 10 list of 'growth' occupations), well none of these require (typically), much if any higher education and of course, also typically offer relatively lower wages than the kinds of jobs of the future we like to think about, (like coding apps, designing wearable computers, or working in high finance).

Yep, according to the BLS anyway, job growth to 2022 is going to be mostly about low-skilled, low-wage, low prospects kinds of service jobs.

Actually the easiest kinds of jobs for the robots to take.

Happy Monday.

Steve

Steve