It's better to have a job when you're looking for a job

As the 2007-2008 financial crisis and subsequent economic recession fade further and further into the distance, we don't in 2017 talk about unemployment all that much. The sustained recovery in the labor market has pushed unemployment to near "full employment" levels of about 4.5% in the US, and in many sectors and job roles most employers would report 'good help is hard to find'. Until the robots take over. But that is a different story for another time.

Back to unemployment though. In 2008 and 2009, there was plenty of discussion about the best ways to help the many, many folks who were out of work to get back into the labor force. Lots of job search gurus appeared online, plenty of networking and support groups were created, and certainly significant governmental support, (cars, banking, insurance), was marshalled to try and stop the bleeding in the labor markets and help get people back to work (or keep them in work).

Around that time, as the unemployment rate topped at about 10%, one peculiar storyline emerged, and pretty consistently as well - namely that folks who were unemployed, and 'actively' looking for work, were often characterized as less desirable candidates than say someone who was currently employed, and may not even be actively looking for something new. The dream 'passive' candidate if you prefer that term. Lots of anecdotes about hiring managers passing on any candidate who was out of work were shared, and plenty of folks, (I possibly was one of them), opined about how unfair that this kind of (for lack of a better word) discrimination against the unemployed was seemingly more and more prevalent. And anecdotal or not, it certainly seemed that looking for a job when you did not have a job was much, much tougher than looking for one when you were already employed.

But just how much tougher is it, really?

A recent study by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York looks to put at least some data around these anecdotes by looking at job search activity by unemployed workers, by employed workers, (both passive and active), and people out of the workforce. The entire report is interesting and worth a read but I thought I would tease out two of the report's most interesting findings about job search, and more importantly, job search outcomes.

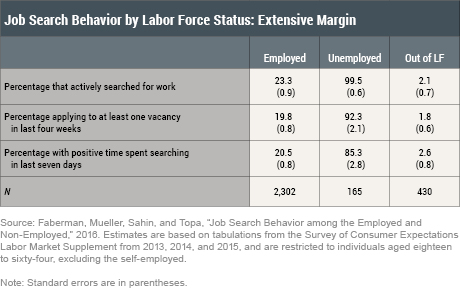

1 - Lots of employed people are actively looking for work - almost one quarter of them 'actively' searched in the trailing four weeks of the survey period

Not shocking I guess, but also the 23.3% doesn't account for the probably much larger number of employed workers that would be open to at least discussing new opportunities, even if they were not in active search. Said differently, one of the reasons contributing to a bias in favor of employed workers is the fact that just about all employed workers are still in the candidate pool anyway. At least partially in.

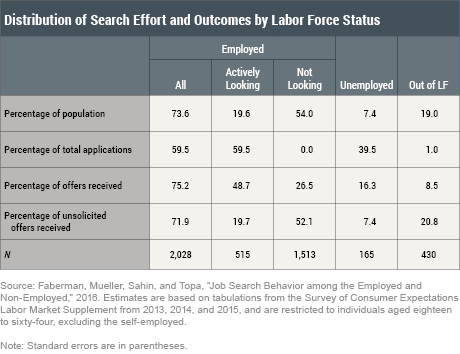

So how does this perceived bias influence outcomes? Here's the money chart from the study, depicting how search behavior and application intensity translate into positive outcomes, i.e. job offers.

I will help you with the fine print here. Unemployed workers make up about 7 percent of the survey sample. They send out 40 percent of the total job applications, but receive only about 16 percent of the total job offers.

In contrast, folks who were employed and were actively looking for work make up about 20 percent of the sample but receive almost half of all offers. Further, the employed not looking for work (and who do not apply for any jobs), receive about one‑fourth of all the offers in our sample—more than the unemployed who are the most active searchers and applicants.

So how much better is it to be employed when looking, (or in many cases not looking) for a new role?

Well, according to this data, much, much better. Roughly it takes eight times the effort in terms of time spent and four times the application rate for unemployed folks to generate a similar rate of job offers that employed workers realize - many of whom are not looking for work at all.

Hopefully we won't have another dramatic economic or market shifting incident like the financial crisis that drives up unemployment and will make these findings and their impacts top of mind again. But it is good food for thought for any of us who may not love the job we have now, and are looking for something better.

We just might want to hold on to that crappy job as long as we can, because having it makes our odds of finding the next (hopefully less crappy) job that much better.

Steve

Steve